|

|

Excerpts from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written

and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth , K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited

by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Tinctures, Divisions and Border Lines (pp.

183-185 and 23 - 26) The oldest escutcheons were as a rule very

simple and bore only two tinctures, a 'colour' and a 'metal'. The charges

were chosen and designed as simply as possible, since the purpose of the

device was to be recognised and identified, even at a distance. For this

reason most of the oldest family coats of arms are uncomplicated in design,

in contrast with the majority of the arms which have been designed since the

Renaissance (see pp. 51, 110, 137). In many cases however the original simple beauty of the coat of arms has been marred by the marshalling of

several devices on a single shield or by augmentations (see p. 54). Ruling princes often combined on the same

shield their family arms with the arms of the countries or territories where

they held sway, or even of countries they did not possess but merely

considered they had a right to, or had once had a right to (until 1801 the

royal arms of Great Britain contained the lilies of France, which had been

included as a quartering since 1340. The three crowns of Sweden are still

included in the Danish royal arms, p. 134).

Such divided and redivided shields were copied by

people not of royal birth who believed that many divisions in a shield

indicated noble ancestry. In the end coats of arms were often composed of

several divisions from the very start (pp. 109

and 110). As an example of this nearly all

the arms of Swedish counts included quarterings and

an inescutcheon (Fig. 766). The simplest coats consist merely of a

shield divided up by one or more lines into fields of two or more different

tinctures. The most important divisions and lines are shown on pp. 24-26 but

the possibilities are virtually limitless. Each different charge can be

further varied by the tinctures used. With merely two tinctures in a coat of

arms it is possible to combine the two 'metals' silver and gold and the four

'colours' red, blue, black and green in sixteen different ways. Charges based

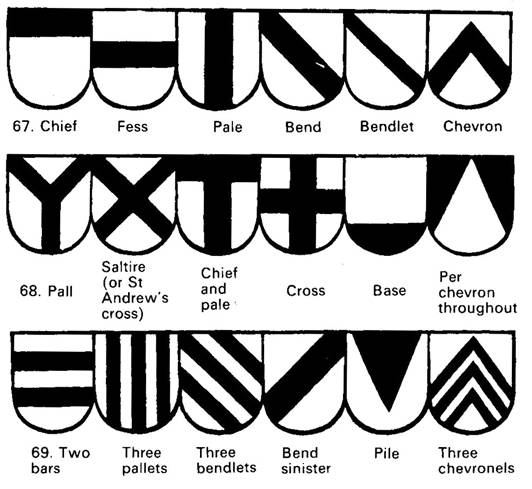

on the commoner divisional lines are called honourable ordinaries and have

their own names: the chief, the bar, the pale, the bend, the chevron, the

canton, the flaunches etc. (see pp. 24 and 25). The

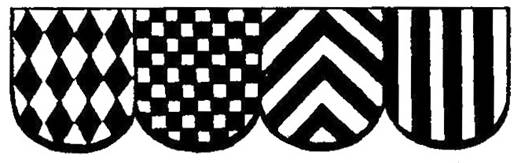

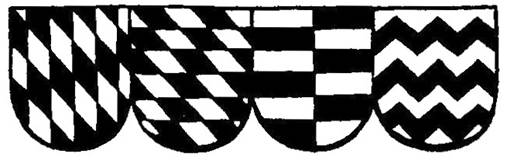

eight divisions as shown on p. 26, Figs 77 and 80,

also have their own concise terminology. (Fig. 77: lozengy,

checky, chevrony, paly. Fig. 80: paly bendy, barry bendy, barry parted per pale, dancetty).

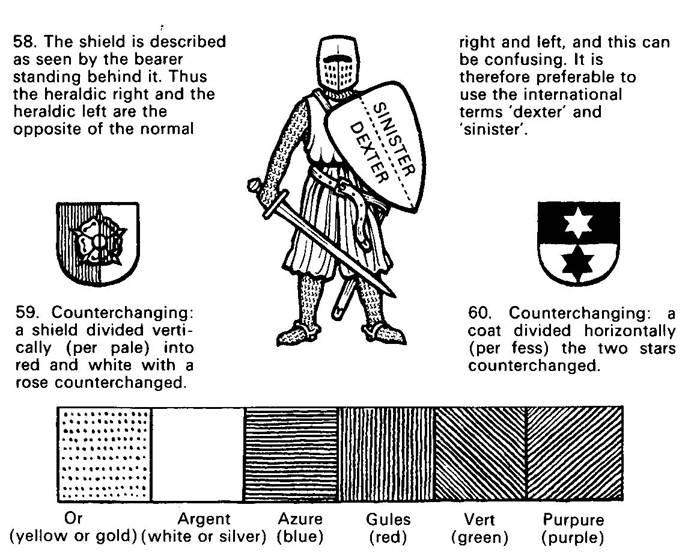

The tinctures of heraldry include the colours

red, blue, black, green and sometimes, but rarely, purple, and the metals

silver and gold. For convenience, white may be substituted for silver and

yellow for gold (see also p. 207). In heraldry of a more recent date it is

also possible to meet with charges in 'proper' colours, as for example a

flesh-coloured arm. TINCTURES

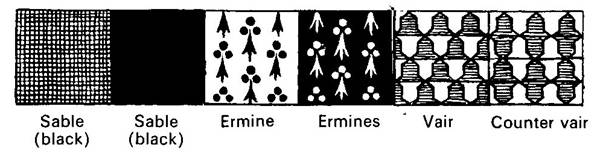

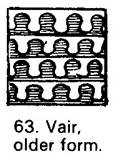

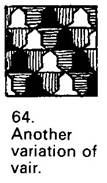

There are as well a number of patterns

called 'furs', ermine and miniver or vair being the most usual (see p. 23). The black tufts in

ermine can be combined in various ways; they represent the black tails of the

ermine or stoat. The white and blue fields in vair

are probably a stylised version of the light-coloured fur on the belly of the

grey squirrel and the darker fur on its back. These patterns in fur ^probably

go back to shields which in the infancy of heraldry were covered with real

fur. See also Figs 293 and 466.

As far as tinctures in heraldry are

concerned the rule is that colour should not be superimposed on colour, but

only on metal, and vice versa (see p. 23). But there are some exceptions. The

rule is for example not applicable to details such as the claws of animals,

hoofs, horns, tongues etc. Fur is 'amphibious* and may be superimposed on

either colour or metal. On occasions the rule is deliberately broken, the

best known example being the shield of the Crusaders' Kingdom of Jerusalem:

on a field argent a cross potent between four plain

crosslets or. But that there is some sense in the rule can be seen e.g. from

the arms of the city of Bonn (Fig. 529), in

which the red lion on a blue field is much less distinct and aesthetically

pleasing than it would have been if the rule had been regarded. See also Figs

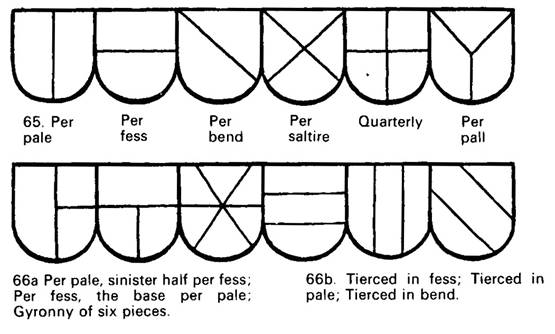

588 and 622. The distinction between certain divisions and

certain ordinaries (p. 24) may seem a little involved. If for example a

shield is divided twice vertically and the outer areas of the fields are of

the same tincture, the field in the middle is called a 'pale' and the whole

is described for example as 'on a field argent a pale sable' (Fig. 67c}. If

the outer areas are of different tinctures, the middle figure is not

necessarily con-sidered an independent charge but

the shield can be described as being 'tierced in

pale' (divided twice vertically into three separate sections) (Fig. 66b,

second example). DIVISIONS AND

ORDINARIES

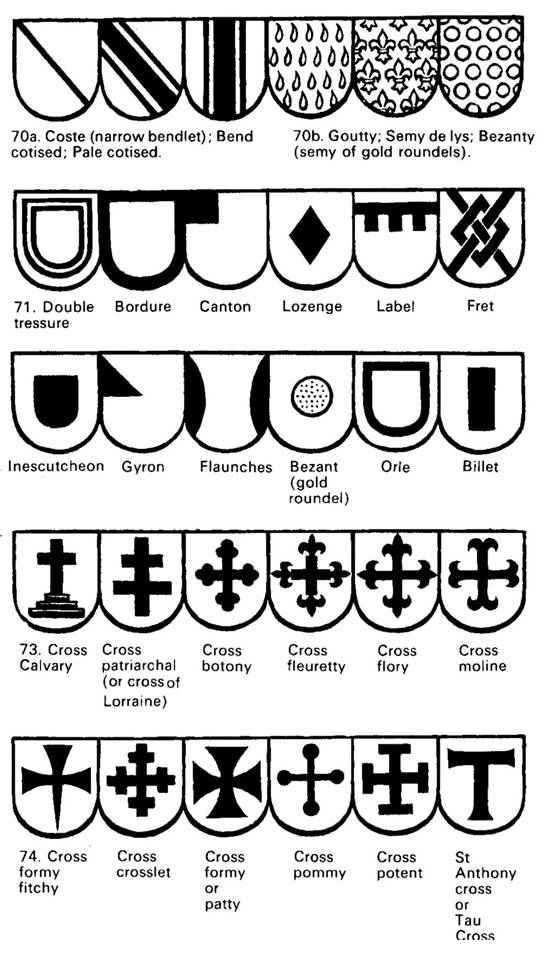

The cross (p. 25) is one of the most common

charges in heraldry and is used in many different forms, only a selection

being shown in this book. A plain, simple cross is found frequently in

Italian municipal heraldry; some examples can be seen on p. 133. The famous

eight- pointed Maltese cross occurs in the achievement of the Order of Malta

(Fig. 278) and appears behind the shield, in

the crown, and hanging from the chain beneath. It can also be seen in the

municipal arms of localities which were once possessions of the Order or in

which some of its properties were situated, as in the arms of Neukoelln, Fig. 522. The

coat of arms of Switzerland is a white Greek cross on a red field (Fig. 593). The principal shield of the Swedish royal

house is divided into four quarters by a yellow cross, and the Danish royal

arms by the cross of the Order of the Dannebrog

(Fig. 723).

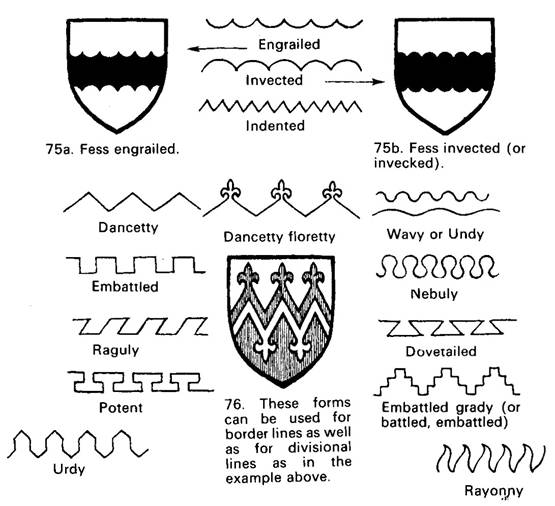

PARTITION AND

BORDER LINES

. |

|

|||||||||||||