|

|

Excerpt from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

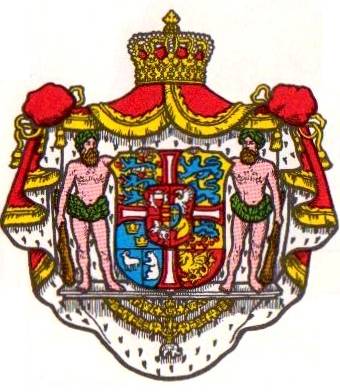

Denmark (pp.

134-137, 216-221) In Denmark the use of an escutcheon in the

traditional sense was probably introduced during the reign ofValdemar the Great (1157-82). It seems more than likely

that the king had armorial bearings containing the three lions (Fig. 727)

which are still the arms of Denmark, in spite of the fact that the oldest

version of them now extant dates from about 1190 and was his son Canute IV's

seal. Two manuscripts, one German and one French,

dating from about 1280, are the earliest to record the tinctures. The small

red charges around the lions are nowadays usually interpreted as hearts - as

the Danish song states, lions leap on the shield and hearts arc afire - but

they actually represent leaves. There were originally many more of them and

their number was uncertain, but in 1819 it was set at nine. The crowns worn

by the lions were added by Valdemar the Victorious

(1202-41), but in every other respect this coat of arms is much the same now

as it was 800 years ago. The arms of the nobility and clergy are

preserved on seals dadng from the second half of

the same century, and those for farmers from around 1300, but all these

various classes may well have had arms previous to these examples which have

only by chance been preserved. The same is true, of course, of coats of arms

for boroughs, districts, guilds and corporations, all of which are known from

seals that go back to the thirteenth century. When speaking of noble and non-noble (commoners')

arms, we should remember that in principle there was no difference originally

between them. It was not until much later with the use of features such as

coronets and the position of the helmet etc. to indicate the holder's rank, that it was possible to distinguish between the arms

of a burgher and those of a nobleman. This in the case of Denmark was after

the inception of the Absolute Monarchy in 1660. The difference was made with

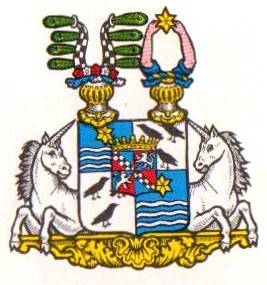

accessories like those mentioned, never with the charges or the crest. The earliest coats were very simple, and

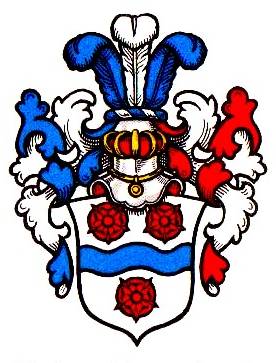

the arms of the family of Brahe are a good example (Fig. 740), but

aristocratic bearings which were obviously made up from two others (such as

those of the family of Ahlefeldt, Fig. 742) are

known from as early as the thirteenth century. During the fourteenth century

the royal family and its branches began to include more than one escutcheon

in their shields to indicate possessions, descent or marriage, and about 1398

King Eric of Pomerania had five coats of arms marshalled on one escutcheon.

These were the arms of his three Scandinavian realms, one for Denmark, one

for Norway and two for Sweden (the ancient Swedish lions and what were then

the comparatively new three crowns of Sweden), as well as his father's* arms

of Pomerania. They were marshalled on a quartered shield with an inescutcheon, and the four quarters of the main shield

were separated by a cross which was no doubt inspired by the Danish flag, the

Dannebrog.

This version of the royal arms was retained

by all subsequent Danish kings. Certain quarterings

were dispensed with, others were added or took their place, but the way this

coat of arms looked up until 1972 (Fig. 723) was in fact a direct

continuation of the combined arms of Eric of Pomerania in 1398. The main

shield is divided as follows: the first quarter contains the arms of Denmark

(see also Fig. 727); the second quarter, Schleswig (see also Fig. 722),

originally a 'reduction' of the arms of Valdemar

the Victorious for his son Abel when the latter was the Duke of South Jutland

(Schleswig); the third quarter, Sweden's three crowns to commemorate the

Kalmar Union, together with the ram of the Faroes

and the polar bear of Greenland, both dating from the seventeenth century. Up

to 1948 Iceland's falcon was also included. The fourth quarter contains two

imaginary charges from the thirteenth century to illustrate the king's

suzerainty over the Goths and Wends. The four quarters of the inescutcheon show the king's titles as Duke of Holstein, Stormarn, Ditmarschen and Lauenburg. The centre shield contains the family arms of

the Oldenburg dynasty, two bars gules on a field or, with Delmenhorst. The

primitive men as supporters were introduced by Christian I in the middle of

the fifteenth century, and the mantling was added at the time of the Absolute

Monarchy. Below the shield are the collars of the Order of the Dannebrog and the Order of the Elephant.|

(On

the accession of Queen Margrethe in 1972 the royal

achievement was somewhat simplified. The arms for the Goths and Wends in the

fourth quarter were eliminated and replaced by Denmark, repeated from the

first quarter; the two inescutcheons were replaced

by a single inescutcheon bearing only the two bars

of Oldenburg; and the limbs of the cross were carried to the edges of the

shield—Ed.) The marshalling of the royal arms was not

the only heraldic innovation of Eric of Pomerania. He seems to have had an

interest in heraldry and perhaps his Queen, Philippa,

shared this interest. She was an English princess, from a court intensely

preoccupied with heraldry, and the granddaughter of John of Gaunt, who had a

considerable influence on heraldic reform in Portugal about this time (see p.

209). The earliest known grants of arms in Denmark to individuals date from

the time of Eric of Pomerania. In 1437 the city of Malmo was granted arms

containing a griffin's head, which was derived from the King's own Pomeranian

charge of a griffin, and this head can still be seen on the lamp-posts and

buses in Malmoe. A number of murals of armorial bearings, including some on

show at Kronborg, date from this time. It was not of course Eric of Pomerania

personally who had these measures carried out. He

had inherited a heraldic organisation with Kings of Arms, heralds and pursuivants which can be traced back to the early years

of the fourteenth century. The kings who succeeded him used the heralds not

only for heraldry, but also for other tasks, especially diplomatic ones. When

the Kalmar Union ended at the beginning of the sixteenth century the office

faded out, although the term 'herald' was retained for certain ceremonial

court officials for about another 300 years. In 1938 an office known as the Statens Heraldiske Konsulent (National Heraldic Advisor) was instituted,

responsible for heraldic issues in the country. Local authorities too have

the right, but not the duty, to seek his advice. In the course of the sixteenth century it

became usual for the nobility to marshal four coats of arms on an escutcheon,

either the arms of the four grandparents or both parents of a married couple.

But these quartered arms were not hereditary. Marshalling several coats of

arms into permanent hereditary armorial bearings really got started after the

Absolute Monarchy had been introduced in 1660. The outcome was that not only

could all existing arms be combined in one escutcheon, but it was also

possible when a completely new coat of arms had been assumed or granted to

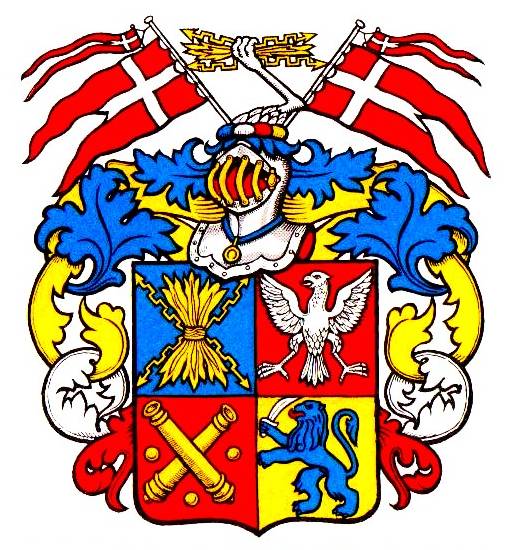

have it divided into several fields. A good example of this is the Tordenskjold coat of arms dating from 1716 (see Fig.

743). The way in which ancient and simple coats of arms were almost eclipsed

by the new fashions can be seen by comparing Figs 742 and 728.

The royal crowns and aristocratic coronets

(p. 135) were introduced with Christian V's rules governing rank and

precedence in the 1670s and 1680s. They were so rigidly defined that

different coronets were specified for use outside and inside the shield (e.g.

on an inescutcheon), but these stipulations were

not adhered to for very long, not even by the royal chancellery which issued

the patents of nobility. In 1679 Christian V gave certain officials ('royal

functionaries') the privilege of bearing a barred helmet, in profile and with

four visible bars, but no Danish king ever attempted to enforce special types

of helmets specifically for the aristocracy.

All the same one often comes across the

expressions 'noble helmet' and 'noble shield' in this period. But apart from

the fact that the barred helmet probably was regarded by many people as the

privilege of the nobility (see Figs 728 and 729), these expressions merely

meant 'a helmet borne by a person of noble rank' or 'a shield borne by a

person of noble rank'. In Denmark, as already stated, there has never been

any difference between the arms of titled persons and those without title,

apart from the coronet, not even during the Absolute Monarchy.

As well as raising many people to the rank of

nobility, Christian V granted a large number of letters patent conferring the

right to armorial bearings, which probably did not imply nobility (the

question has been under discussion), but the great majority of middle-class

arms - for the clergy and men of learning, officials and officers,

businessmen, craftsmen, printers and apothecaries and so on - continued to be

self-assumed. How many there are is difficult to say. The aristocratic arms

are accountable: there are something between 1,700

and 2,000. But there are far more of the others, at least 8-10,000. In

comparison with other countries, such as Sweden, Holland and England, this is

a relatively small number, and this is no doubt partly a result of the fact

that the farmer class had no influence on political life, anyhow from the

time of the civil war known as the Feud of the Count, 1534—36, partly a

consequence of the near-impotence politically of practically all classes of

the community during the Absolute Monarchy (1660—1849). However, the arms of commoners

are often more attractive than those of the aristocracy, mainly because they

are usually less intricate (Figs 738 and 739). In the course of the eighteenth century and

the first half of the nineteenth interest in heraldry diminished at the same time

as heraldic taste deteriorated (by modern standards). In the second half of

the nineteenth century scholars began to develop an interest in heraldic

matters, and this resulted among other things in tomes of publications on

seals preserved from the Middle Ages, the majority of which were heraldic,

and this interest became more widespread. Most of the market towns had had a

device since the Middle Ages, mostly on a seal. Now it became the fashion to

set this device on a shield and choose suitable colours. The result was not

always a happy one as far as the best heraldry goes, because the figures on a

seal - engraved on a small scale and intended to stand out in relief in only

one colour - are difficult to transpose into the forms and colours of

heraldry (Figs 720 and 741), but the interest was there and sometimes the

results were splendid (Figs 721 and 744). New local authorities have

increasingly adopted armorial bearings, some 200 since 1900 (see Figs 745 and

746).

In 1959 the Heraldisk

Selskab, embracing the whole of Scandinavia, was established.

Today it has nearly 600 members, a good third of whom are Danes. The

activities of the society include the publication of the journal Heraldisk Tidsskrift. A

specimen copy and other information can be obtained free from the secretary

of the society: Dr Ole Rostock, Sigmundsvej 8, 2880 Bagsvaerd, who also accepts

applications for membership. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||