|

|

Excerpt from the

book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Poland, Lithuania and Belarus (pp.

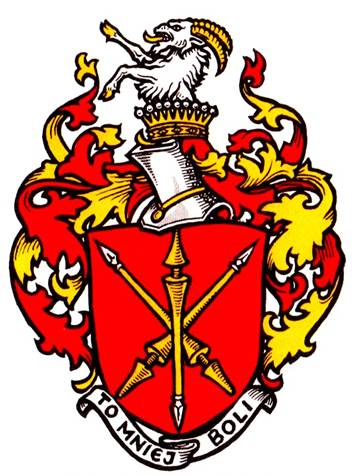

148-151, 229-231) Polish heraldry differs considerably from

that of other countries, both in its appearance and its system. - Most of the

divisions and charges common to the rest of European heraldry (bend, bar,

pale etc.) are almost unknown in Poland. On the other hand many Polish coats

of arms have various rune-like and cipher-like charges which are unknown

elsewhere (see p. 150 / Fig.801). In many cases such emblems have become a

form of heraldry (probably to facilitate description) consisting of

horse-shoes, half-moons, crosses, arrows etc., but there is little doubt that

such arms are closely connected with original cipher arms. Fig. 796 is a good

example; its three tournament lances may well once have been a simple figure

of three straight lines, something like an X superimposed on an I. There is no consensus among experts about what lies

behind the idea of these figures, but most agree that they go back to some

form of cipher.

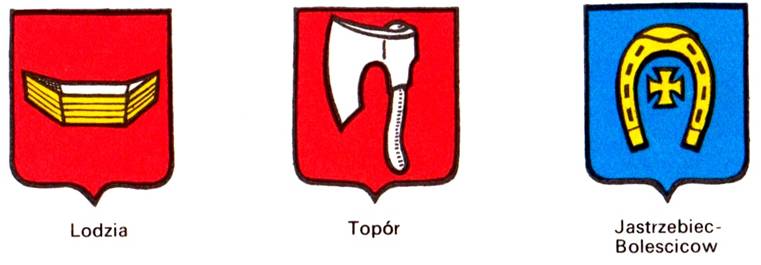

Another special feature of Polish heraldry are the so-called proclamatio arms. By this is understood

armorial bearings common to several noble families, each with its own

name and as a rule having no family relationship with one another. Some of these proclamatio arms are common to

more than a hundred families. The record is probably held by the horse-shoe

enclosing a cross which is common to 563 families (see Figs 805 and 804c).

These arms held in common, or arms of family groups, like all coats of arms

of Polish families of ancient lineage, have their own nomenclature, usually

different from the names of the families that bear them. Their designation is

at times the word for the device itself, but most of them might well be old

rallying or war cries used in the past by a family

group, clan or tribe. The Latin word for war cry is proclamatio, and it is from

this that the group of arms takes its name. It may be another instance of this

organisation into family groups that ennoblement in Poland often took the

form of adoption. Instead of a person for example being raised to the

nobility by royal patent, he was adopted into a family that was already

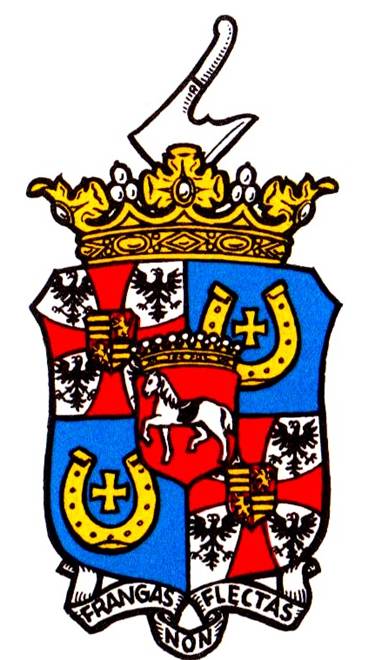

noble. Fig. 797 shows the arms of a family (Wielopolski

(-Gonzaga)-Myszkowski), adopted by the Italian

princely family Gonzaga in Mantua, whose arms can be seen in the first and

fourth quarters of the principal escutcheon.

797. Arms of the

Marquises Wielo- polski

(-Gonzaga)-Myszkowski. The inescutcheon is the hereditary coat of arms belonging to

the Staryikon group. This procedure is perhaps connected with

the extraordinary standing of Polish nobility. All Polish noblemen were in

theory equal, and it was particularly the less well off among them, the Szlachta, who

tried zealously to prevent the Polish kings from introducing orders of precedence

within the aristocracy. The majority of Polish titles—baron, count, marquis,

prince — are of foreign origin, especially German, Austrian, Russian and

Papal. Native Polish titles, granted by the kings, were extremely rare and

seldom hereditary. But Polish kings could on the other hand invest foreigners

with Polish titles of nobility. In the coats of arms in Figs 796, 802 and

805 the coronet is set on the helmet, but just as frequently we find it ensigning an inescutcheon (see

Fig. 797), in which case there may also be a coronet on the helmet. Barred

helmets were as likely to be used as the tournament helmet shown in the three

examples. There are thought to be at least 5,000

Polish coats of arms. There may be even more burgher and farmers' arms, a few

of which date back to the thirteenth century, but the majority come from the

sixteenth century and later, and in addition to these there are over 1,000

ancient city and rural arms. Most of the burgher and civic arms have been

lost as a result of Poland's unhappy history.

By the Partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793

and 1795 the country was in turn swallowed up by Russia, Austria and Prussia,

and one of the expressions of Polish

nationality which was subsequently suppressed was its heraldry. Russia was

particularly guilty in this respect. When in the nineteenth century the

Czarist regime reluctantly gave ten Polish administrative districts

permission to have coats of arms, it was on the condition that these armorial

bearings should in no way contain or even be reminiscent of the older devices

of these localities. The Germans

during the Second World War tried to find the ancient Polish civic seals and

those discovered were destroyed. All the same not everything had been

destroyed or forgotten. When after the First World War Poland had once again

become independent, the use of many old city arms was resumed and new civic

arms were created. What the situation is like today is not certain. But

Poland, alone of all the Communist countries, still uses its old coat of

arms, a white eagle on a red field. These were originally the armorial

bearings of the Polish kings and can be traced right back to the thirteenth

century. The bordure, which can be seen in Fig. 795 and which is inspired by

Polish military uniforms, was only used between the two wars. After the last

war the crown, which the eagle had borne since the Middle Ages, was omitted.

________________________ PS.: For those who can read in Russian, the

below book may be interesting as well because it covers the mottoes in both

Finnish and Russian heraldry: ГЕРБОВЫЕ

ДЕВИЗЫ

РУССКАГО,

ПОЛЬСКАГО,

ФИНЛЯНДСКАГО

И ПРИБАЛТIИЙСКАГО

ДВОРЯНСТВА C.H. Тройницкiй Изд. Сiриусъ,

С-Петербургъ

1910 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||