|

|

Excerpt from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||

|

|

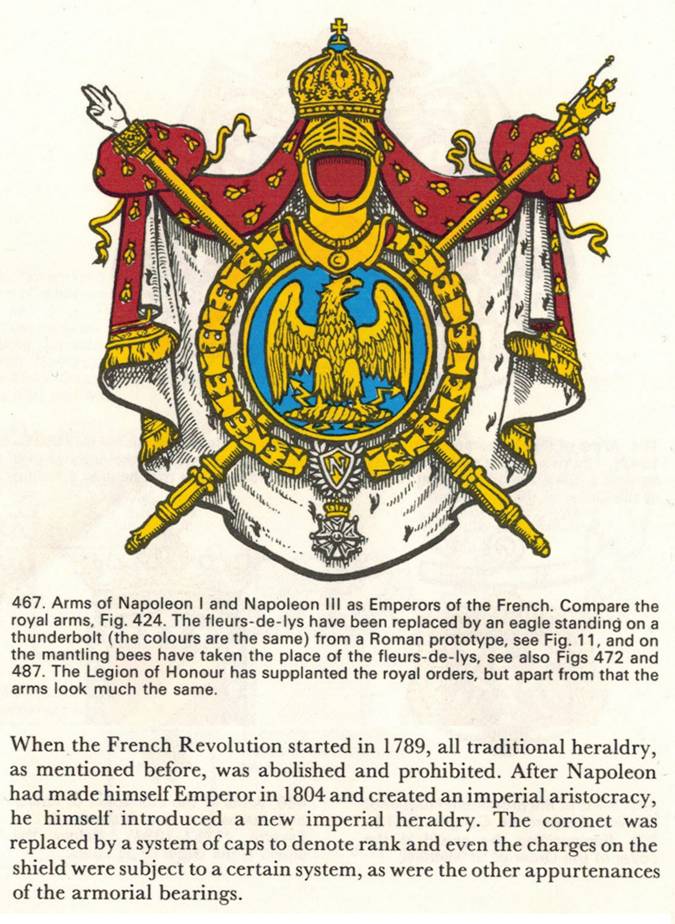

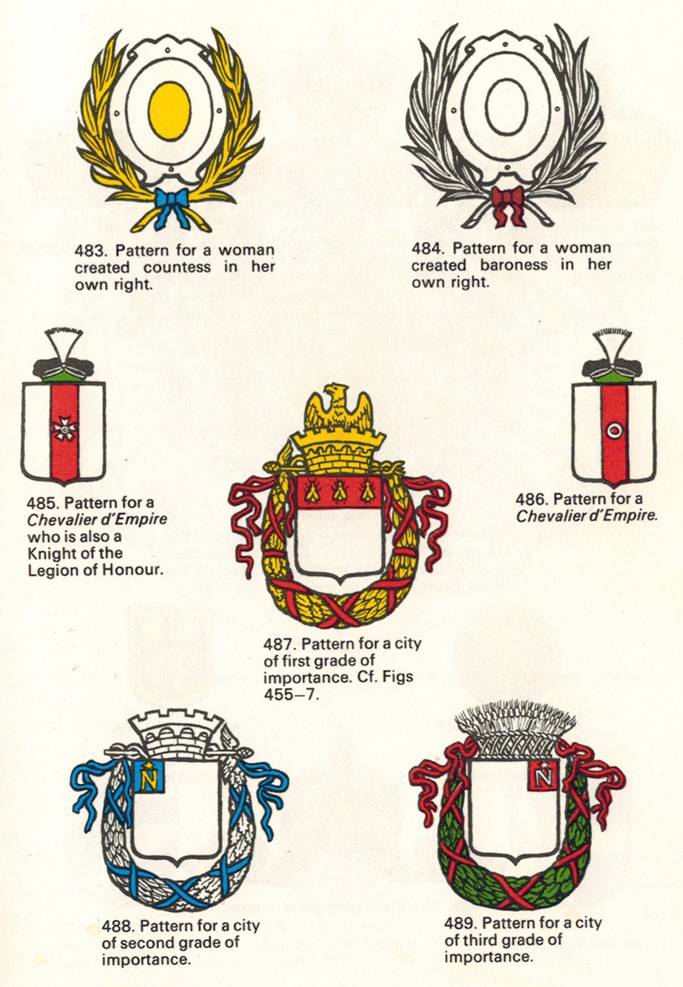

Napoleonic Heraldry (pp.

90-93 and 200-202) When Napoleon became emperor in 1804 he did

not assume the arms of the Buonaparte family (Fig. 469) as his imperial escutcheon, but

adopted a completely new one: an eagle with a thunderbolt in its claws,

clearly inspired by the eagles of the ancient Roman legions (see Fig. 11). For his new, imperial aristocracy Napoleon

devised a heraldic system which was to some extent based on the old heraldry

from before 1789, but which at the same time contained many new details and

was different because of the standardisation, or even compartmentalisation,

it symbolised. The idea behind the system was that it should reflect the

Napoleonic state, especially the army, and this new heraldry became so

regimented in its categories that the individual characteris¬tics

of the various coats of arms almost disappeared. The stereotyped patterns

given as examples on pp. 91-3 show the empty shields which were all that was

left for the personal arms of the holder. It was the same with civic heraldry

(Figs 487-9). Furthermore, even in those cases where there was a free choice

the designs became very repetitive, because so many people chose the same

bearings: sabres, swords, cannon, grenades, pyramids, bridges and suchlike,

inspired by the campaigns of those days. The royal fleurs-de-lys disappeared completely and were replaced by bees

(Figs 467, 472 and 487).

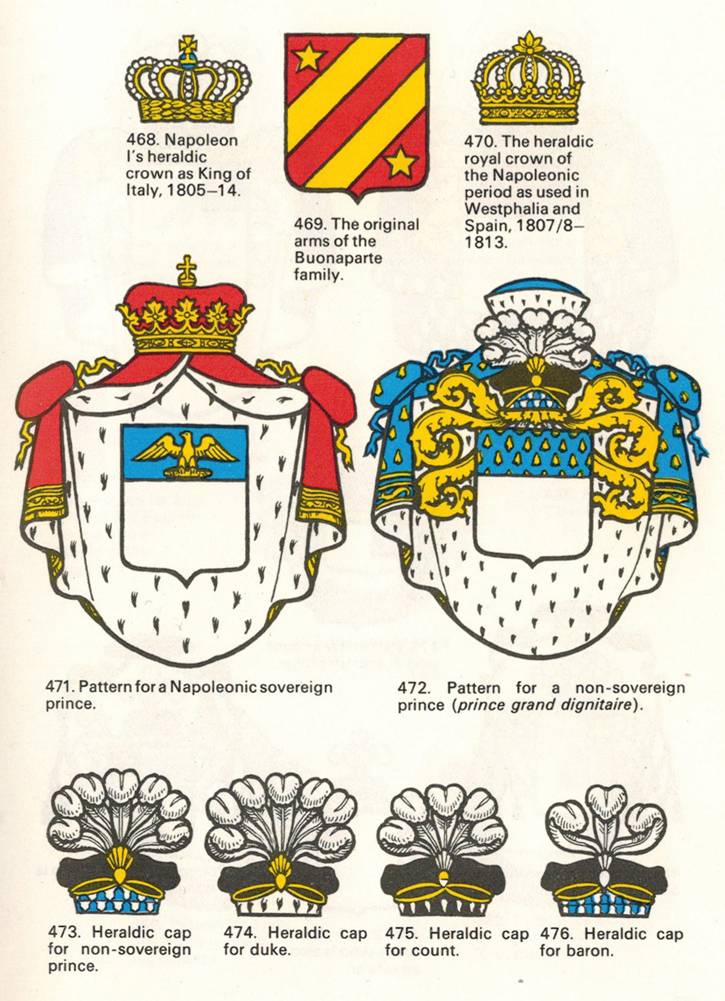

Helmets and crests as well as supporters

and mottoes were excluded. The coronet was replaced by a black velvet cap or

‘toque’ (French: barrette) (pp. 91 and 92). The fur at the edge, the clasp at

the front and the number of white ostrich feathers indicated the rank. Both a

non-royal prince and a duke had a gold clasp and seven plumes, but the prince

had an edging of miniver (or ‘vair’),

in contrast to the ermine edging of the duke (Figs 473 and 474). A count had

an edging of ermines (white spots on a black field, see Fig. 62), with a

clasp half of which was gold and the other silver, and five plumes (Figs 277

and 475). A baron had an edging of counter-vair, a

silver clasp and three plumes (Fig. 476). The cap of a knight (chevalier) had

green edging and a single tuft of white horse hair (Figs 485 and 486). The highest ranks had mantles or robes of

estate. A non-royal prince’s mantle was blue strewn with gold bees and

surmounted by another cap with ermine edging (Fig. 472). A duke’s mantle was

blue with a lining of vair, while the mantle for a

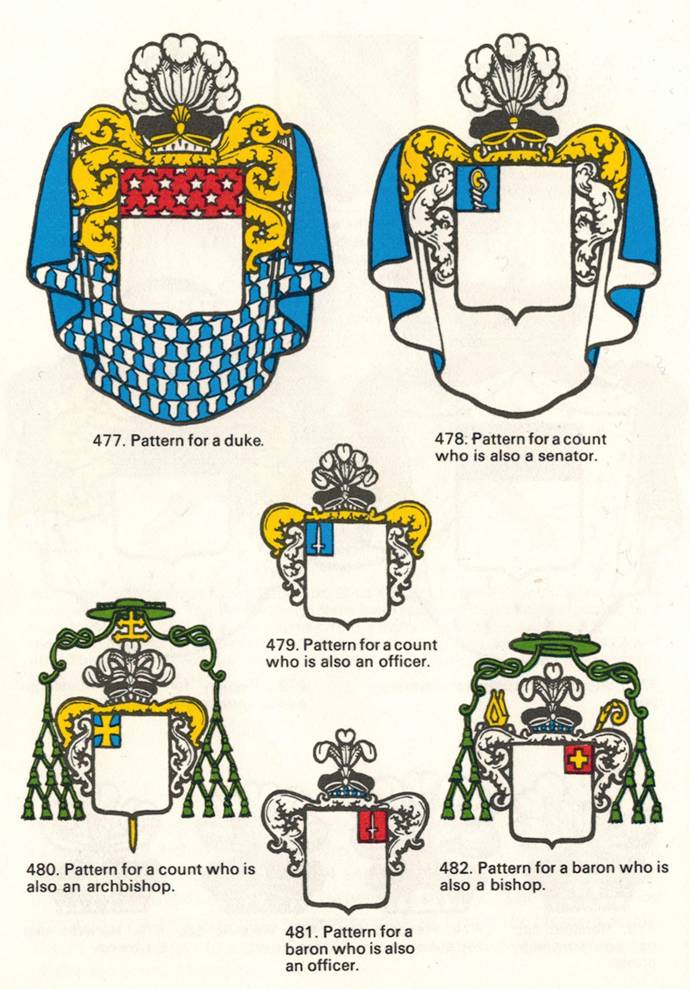

count who was also a senator was blue with a white lining. Embellishments reminiscent of mantling or

lambrequins issued from the cap of rank (p. 92). Princes and dukes had six of

these, all gold. Counts had four, two gold, two silver.

Barons had two silver, and knights had none. With the aid of specified content and

tincture classification could be carried even further. All non-ruling princes

had a blue chief strewn with yellow bees (Fig. 472), and all dukes had a red

chief strewn with white stars. All counts had a blue dexter

canton with an emblem which further indicated their position in life e.g.

senator, officer or archbishop (Figs 478, 479 and 480). All barons had a

similar, but red, sinister canton (Figs 481 and 482). Knights of the Legion

of Honour bore the cross of the Order on a red ordinary, usually a pale or a

fess (Figs 285 and 485). See also Italy, p. 213. Women bore oval shields between two palm

branches, gold with a blue knot for a countess, silver with a purple bow for

a baroness. Both categories had also an oval inescutcheon,

yellow for a countess, white for a baroness. In civic heraldry there were three grades

of ‘important towns’, and the attributes of their

rank can be seen in Figs 487-9. With the return of the monarchy this

heraldry disappeared from the official scene until it was revived under

Napoleon III (1852-70). |

|

|