|

|

Excerpt from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth , K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||||||||||

|

|

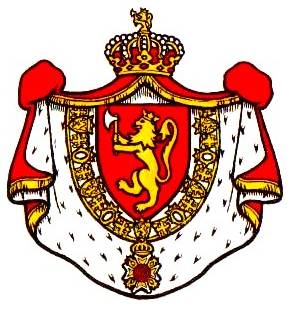

Norway (pp.

138-139, 221-223) The royal arms of Norway can be traced back

to Haakon IV Haakonson (1217-63). Like so many

other European rulers he took a lion as his device, gold on a field gules. In

the 1280s King Eric the Priest-Hater gave the lion an axe, the attribute of

St Olav, the patron saint of Norway, between its front paws, but no change

has since taken place and in its present form as a shield without the

addition of other arms or quarterings it is one of

the simplest and most beautiful national coats of arms in Europe (Figs 747

and 750; with reference to the axe see also Fig. 749).

Arms were adopted by others apart from the

royal family during the thirteenth century. The oldest extant example is on a

seal belonging to a knight, Basse Guttomson, and dates from 1286. In the course of the

following fifty years the number of persons and families with armorial

bearings greatly increased, but in 1349 Norway was afflicted by the plague

known as the Black Death. As well as the dire consequences it had for

Norwegian economic and cultural life, heraldry stagnated, and few new coats

of arms are known from the subsequent period. In 1380 Norway was united by

personal union with Denmark (this lasted until 1814), but the seat of

government was in Denmark, and many of the coats of arms which are known from

Norway in the following century are really Danish. But the Norwegian farmers

developed a form of personal heraldry in cipher, often with both shield and

helmet and sometimes with regular heraldic charges. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

Norwegian trade increased and many foreigners arrived in Norway. The

Dano-Norwegian kings began to accept citizens of merit into the aristocracy,

and this increased greatly after the introduction of Absolute Monarchy in

1660 (see the arms of the family of Wcrenskiold

from 1697, Fig. 754, and those of Tordenskjold from

1716, Fig. 743). According to Christian V's rules of precedence it was,

between 1693 and 1730, sufficient to reach the highest level of rank to be

regarded as an aristocrat. For details of coronets, the special helmet for

the 'royal functionaries', and Christian V's letters patent, see the text

under 'Denmark’, p. 219. The same text deals with the organisation of heralds

in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, since this was common to both

Denmark and Norway; one of the realm's two Kings of Arms held the title

'Norway'.

Most of the Norwegian family coats of arms

date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly from the

period after 1660, when the introduction of Absolute Monarchy had

strengthened the position of the middle classes. Some of the armorial

bearings belonged to purely Norwegian families such as the Bulls (Fig. 751),

others to immigrant families like the Griegs (Fig.

753), who came from Scotland, and in fact Scotland had a noticeable influence

on Norwegian heraldry from its very beginnings.

On the part of the authorities there was

never any desire to exercise control over heraldry at all. There was complete

freedom to do what one liked, and this was taken advantage of in Norway to an

even greater extent than in other countries. Not only were coats of arms

self-assumed, but they were also altered, so that inherited arms were

completely changed or took on a new form. Even in the Middle Ages it had been

usual for a son to have a different coat of arms from his father, and for

brothers to possess different armorial bearings. Now it became customary for

the principal features of a coat of arms alone to be inherited, while details

were removed or added, so that each, coat assumed the character of personal

bearings. Inheritance of arms through the distaff side was quite common, even

if the male line already bore arms, especially when the mother was of a

higher social standing.

Another feature, known in other countries

as well, but especially frequent in Norway, was for a person, because of a

chance similarity of name, to assume the arms of another, unrelated family,

particularly if the latter family had died out. A number of Norwegian civic coats of arms

date from mediaeval or later seals. The arms of the city of Oslo provide an

example of this (Fig. 752). They show St Hallvard,

the patron saint of the city, with the instruments of his martyrdom, the

arrows he was killed by and the millstone tied around his neck when

afterwards he was thrown into the water. At the base of the shield lies the

girl whom he tried to rescue from her persecutors. As in so many other

countries Norwegian civic heraldry has boomed tremendously in recent decades.

The interest taken by counties and local authorities is considerable, and a

number of fine bearings have been composed.

752. City arms of

Oslo. This growing interest in heraldry in Norway

has also found expression in the establishment a few years ago of the Norsk Heraldisk Forening (which is affiliated with the Scandinavian Heraldisk Selskab, see under

'Denmark'), with some 100 members. Further information can be obtained from

the secretary of the association: Hans A. K. T. Cappelen,

Bygdøy Allé 123 B, Oslo

2. (The above review of heraldry in Norway is

based mainly on Hans A. K. T. Cappelen's work Norske slektsvåpen,

Oslo 1969.) |

|

|||||||||