|

|

Excerpt from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||

|

|

Italy (pp.

126-133 and 213-216) In order

to understand the many foreign influences that are found in Italian Heraldry,

it must be remembered that for practically the whole of its history the

country has been the background for power struggles by foreign states, and

that in fact large parts have been ruled by directly from abroad or by

foreign princely houses for very long periods.

From 1194

Southern Italy belonged to the German Hohenstaufens.

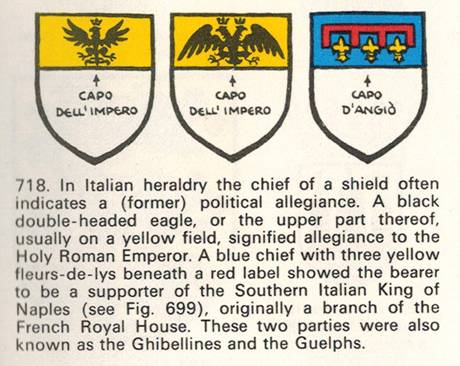

In 1266 it was conquered by Charles of Anjou, a French prince (see Fig. 718),

whose descendants ruled the country during the following centuries. In 1504

Spain took possession of Naples, which became a bridgehead for Spanish power

and influence in Italy for almost 300 years. At the close of the eighteenth

century the Spanish were superseded by another collateral branch of the

French dynasty who gave this Southern Italian kingdom the name ‘The Two Sicilies’.

Central

Italy consisted mainly of papal possessions with Rome as their centre, and in

Northern Italy there developed in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries a

number of rich and powerful city states, of which Genoa, Florence, Venice and

Milan were the most important. But in 1494 Northern Italy was turned into a

battlefield on which the Habsburgs, Spain and France fought for the wealth of

Italy. In 1540 the Spaniards took Milan and this, combined with their

occupation of Southern Italy and Sicily, gave them the upper hand in Italy

during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1713 however the most

important of the Spanish possessions in Northern Italy were ceded to Austria,

which then became the dominant power until the French revolutionary armies

forced their way across the Alps in 1792. In 1796 Napoleon conquered Lombardy

and in 1805 he made himself king of Northern and Central Italy. His stepson,

Eugene de Beauharnais, became viceroy of Italy and introduced the Napoleonic

system of heraldry (see pp. 90-3).

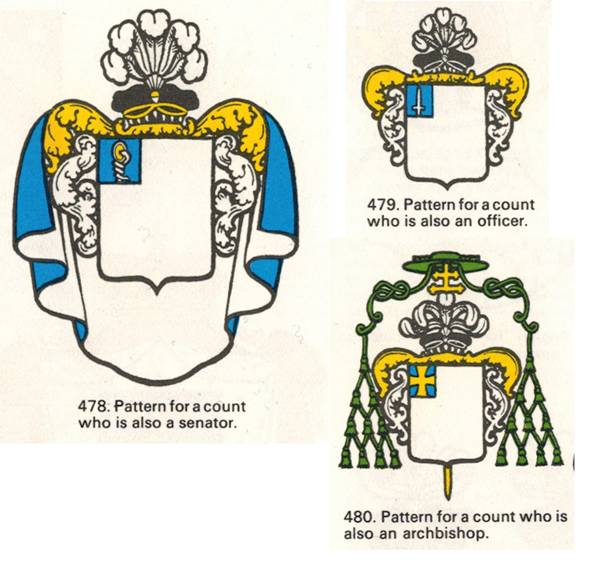

Theoretically

Italy was not a part of the French empire but an independent kingdom, and

attempts were made to emphasise this by permitting Napoleonic heraldry as

used in Italy to diverge somewhat from the French. For example, in France the

Napoleonic counts bore a small blue canton containing one charge or another

(see Figs 478, 479 and 480). This canton was green in Italy, corresponding to

the newly-created Italian flag which was striped vertically green, white and

red in contrast to the blue, white and red of the French tricolour.

After the

fall of Napoleon Austria once again took control of Northern Italy, but in

1848 Piedmont began its fight for liberty, and with the help of the French,

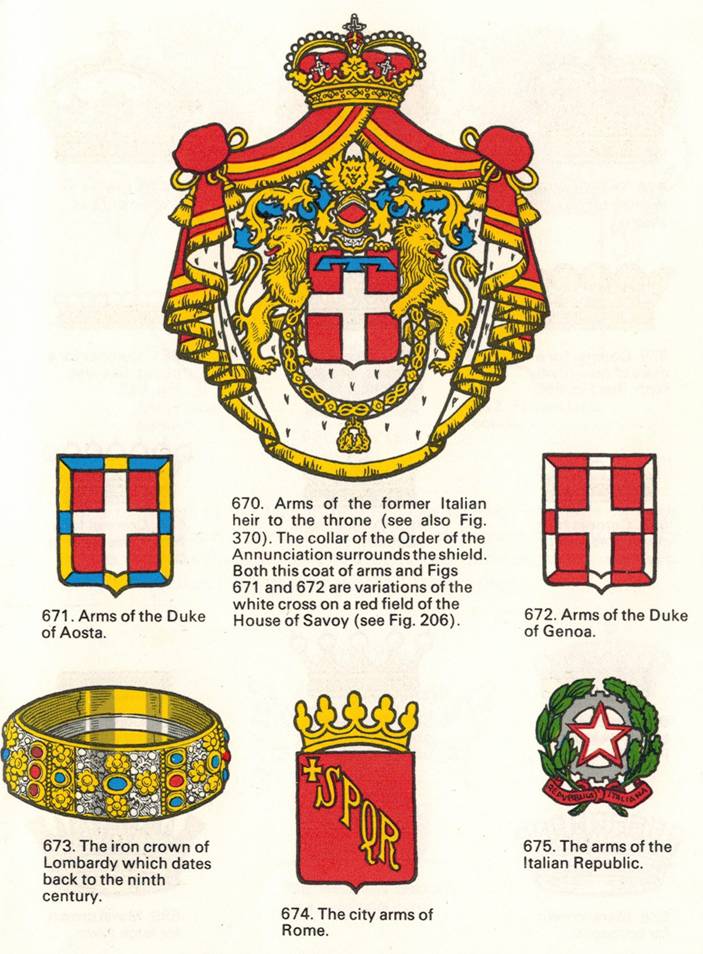

the Austrians were driven out of Lombardy in 1859. This fight for freedom

spread throughout the whole of the country, and in 1861 Victor Emanuel II of

Piedmont and Sardinia, of the House of Savoy, was hailed as king of a united

Italy. In 1946 King Victor Emanuel III abdicated in favour of his son Umberto

II who ruled until 13 June 1946; he left Italy but never renounced his

rights. During the

monarchy a heraldic administration was set up which dealt with the whole

country, the Heraldic Tribunal or Consulta Araldica. This was abolished by the republic, and

later the National Heraldic Council for Italian Nobility or Consiglio Araldico Nazionale del Corpo della Nobilta Italiana was instituted on a private basis, its

functions including the registration of noble armorial bearings. In 1853 the Collegio Araldico

was established in association with the Holy See and this also is mostly

concerned with the aristocratic side of heraldry.

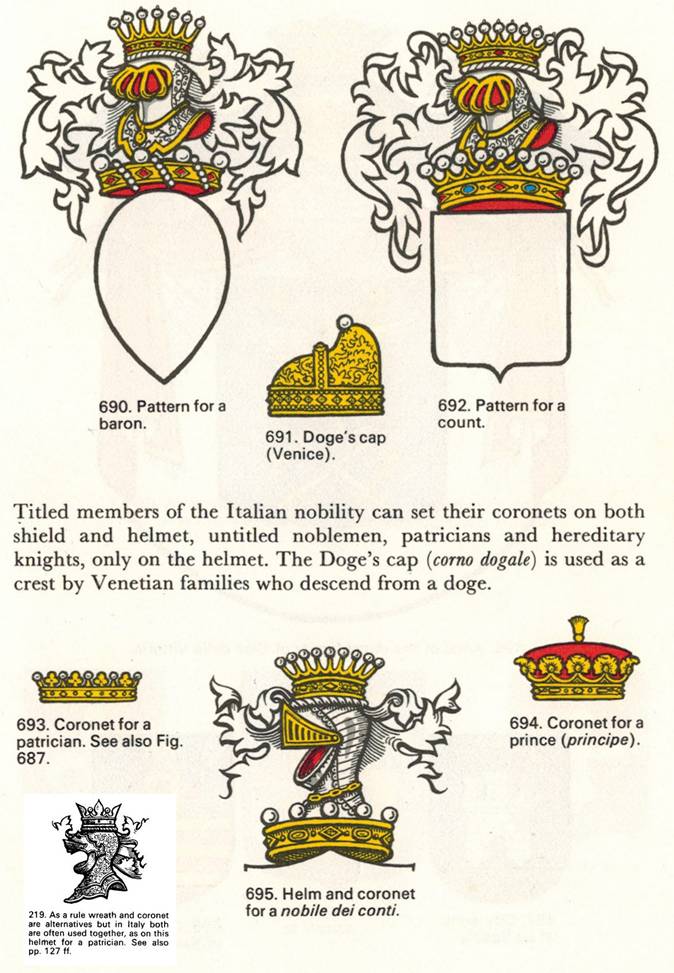

As well as

all the usual forms of shield, a number of shapes are used in Italy which may

be seen in other parts of Europe, but which nevertheless are very

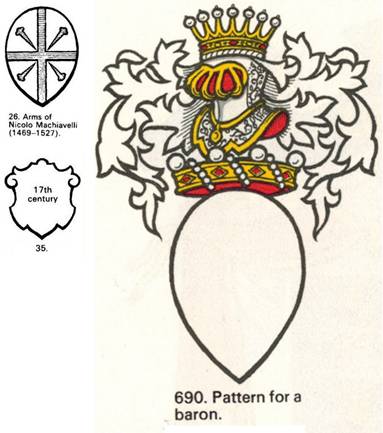

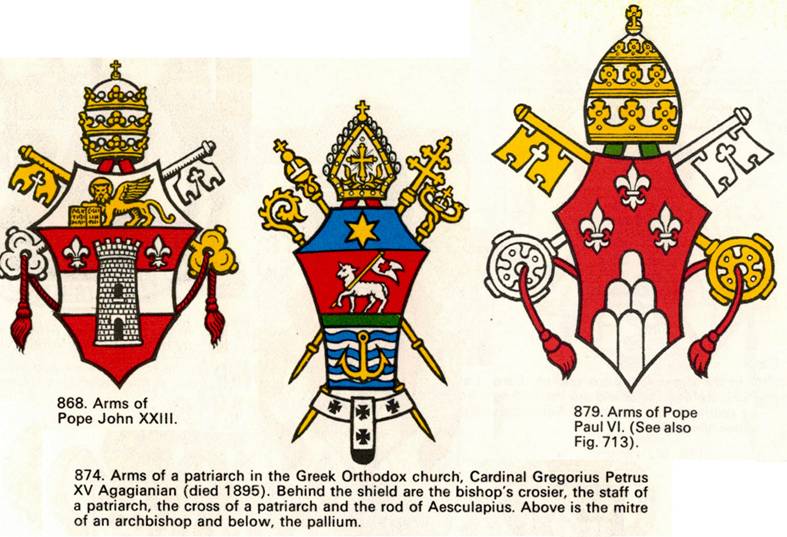

characteristic of Italy. Among these are the almond-shaped shield (Figs 26,

35 and 690) and the so-called horse-head shield (Figs 868, 874, 879 and 899).

The latter is reminiscent of a horse’s head seen from the front, and it is

very likely that small shields like these were placed on the foreheads of

horses at tournaments. Women’s shields are often oval.

The

illustrations of noble and other armorial bearings on pp. 125-33 show how

they should look ‘officially’. Consulta Araldica realised however that many foreign

influences had gained a foothold over the years, and accepted that a wide

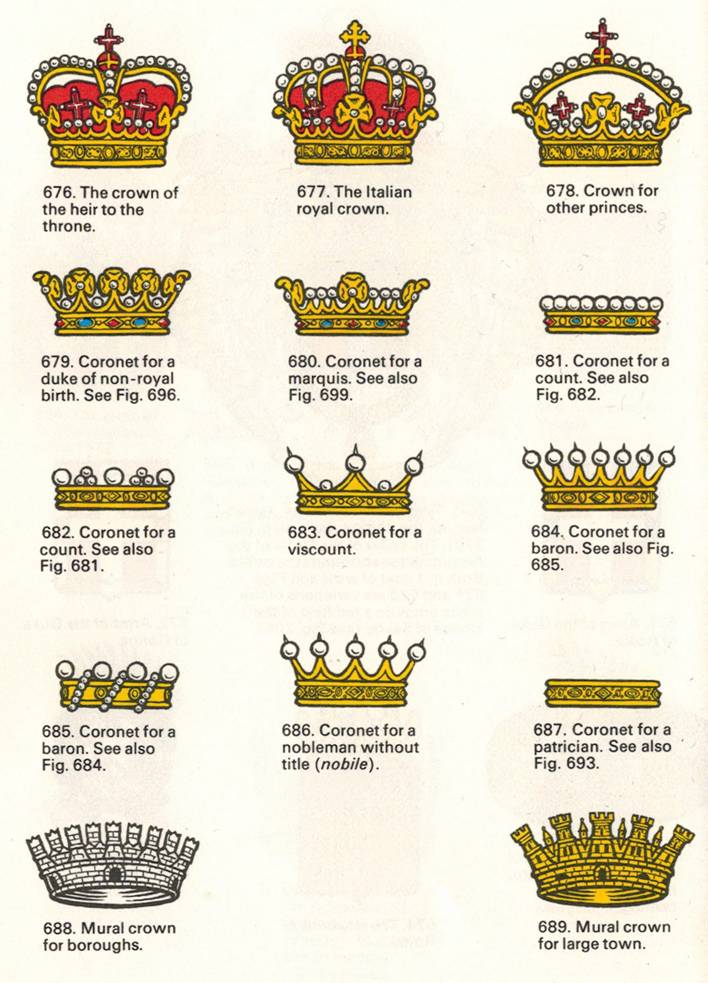

variety of choice in heraldry was now an established fact. The various

heraldic systems each had its own type of coronet, and in continuation of a

practice dating from the eighteenth century it was permitted to bear in the

same coat of arms two different coronets to indicate rank, one above the

shield and one on the helmet (Fig. 690). In fact it is possible to have two

different coronets showing different ranks, e.g. if one belongs to a family

whose head bears a higher title than oneself. In that case the personal

coronet is borne above the shield and the superior rank of the head of the

family is shown by the coronet on the helmet (Fig. 695).

Another

peculiarity of Italian heraldry is the use of both wreath and coronet on the

helmet. In most other countries one of these is usually considered sufficient

(pp. 36 and 39-40). The Italian wreath is however very slim in comparison

with that of other countries and is easily overlooked (Fig. 219 and pp. 127 ff). Supporters

are rare. When they occur it is usually in the arms of the higher

aristocracy, but there seem to be no rules for their use, and in fact it is a

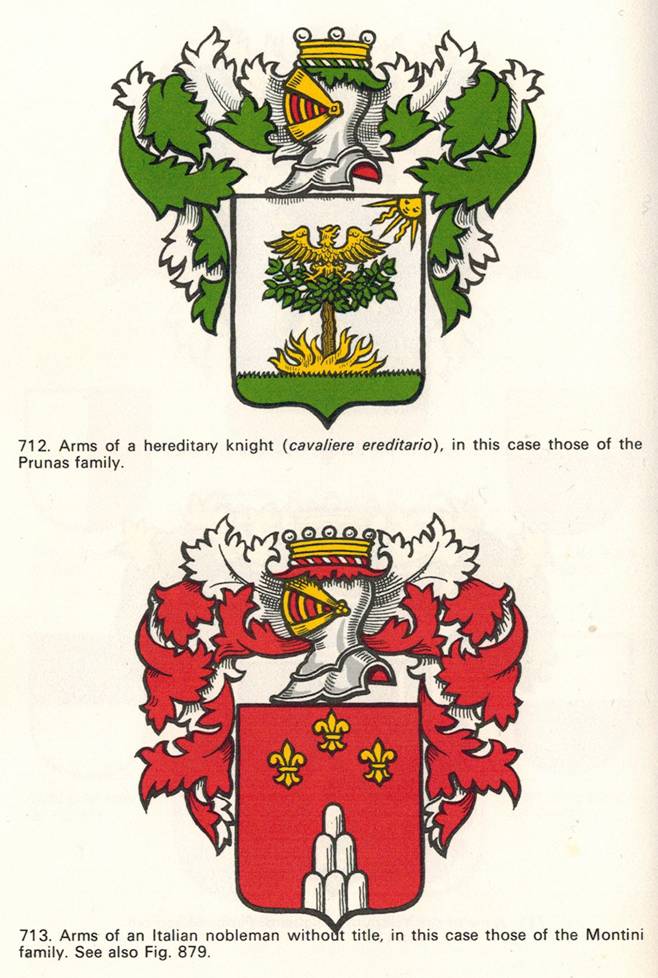

case of do-as-you-please. Under the

monarchy the Consulta Araldica registered

not only coats of arms of the nobility but also those of ‘outstanding’

bourgeois families who could prove that they had borne arms for at least a

century. Besides these there must be a large number of non-aristocratic arms, especially

in Northern Italy. The helmet for a commoner's arms is 'iron-coloured' and visored, with the visor lowered, shown in profile (see p.

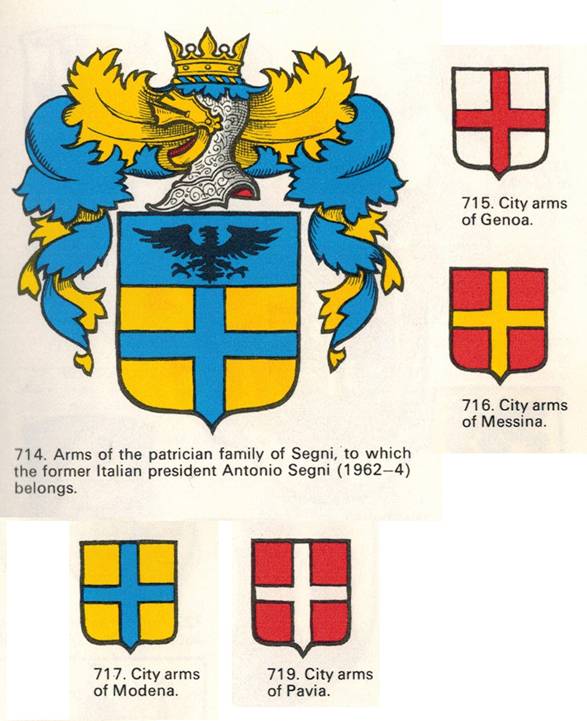

19). Crests are rare in Italy, and are not used by commoners. A 'patrician' is comparable with an

untitled nobleman. His helmet is steel- or silver-coloured with raised visor

in gold, shown in profile (Fig. 714), and often chased and ornamented. There

are many different patrician coronets. This book shows three (Figs 687,693

and 714), and there is also a special Venetian patrician coronet. The helmets of the nobility are silver with

visor and bars in gold. The more bars there are (pp. 127 ff.), the higher

seems to be the rank of the bearer, but there appear to be no definite rules.

In fact, any sort of helmet may be used by all classes. Fig. 695 shows a

typical form, a visored helmet in profile with only

the lower part of the visor open. The helmets of the royal family were

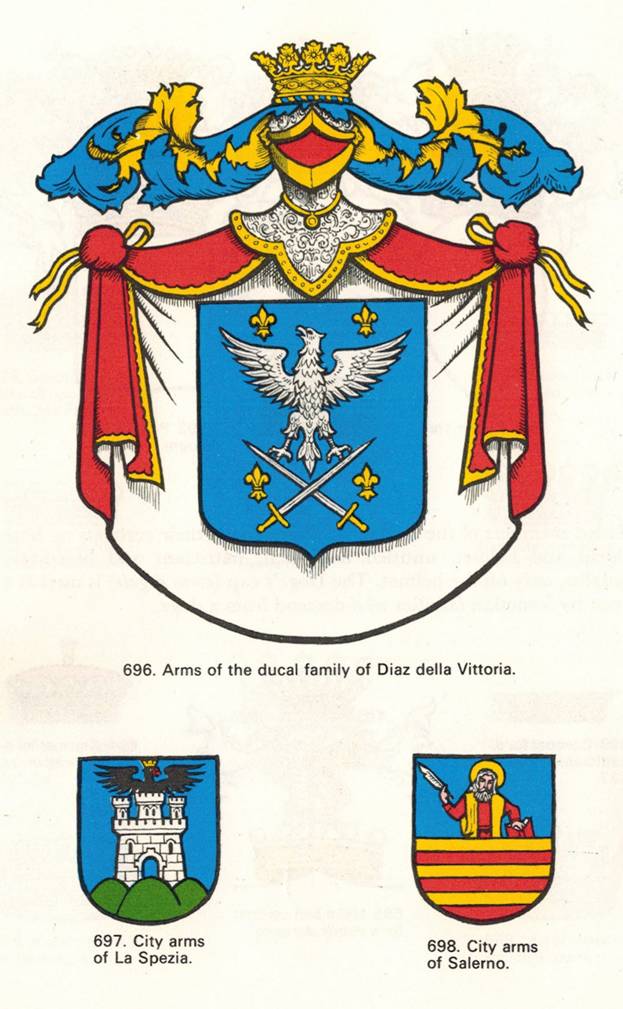

golden. The clergy and women have no helmet. Princes and dukes who have a mantle or robe

of estate can set their helmets together with appurtenances on top of the

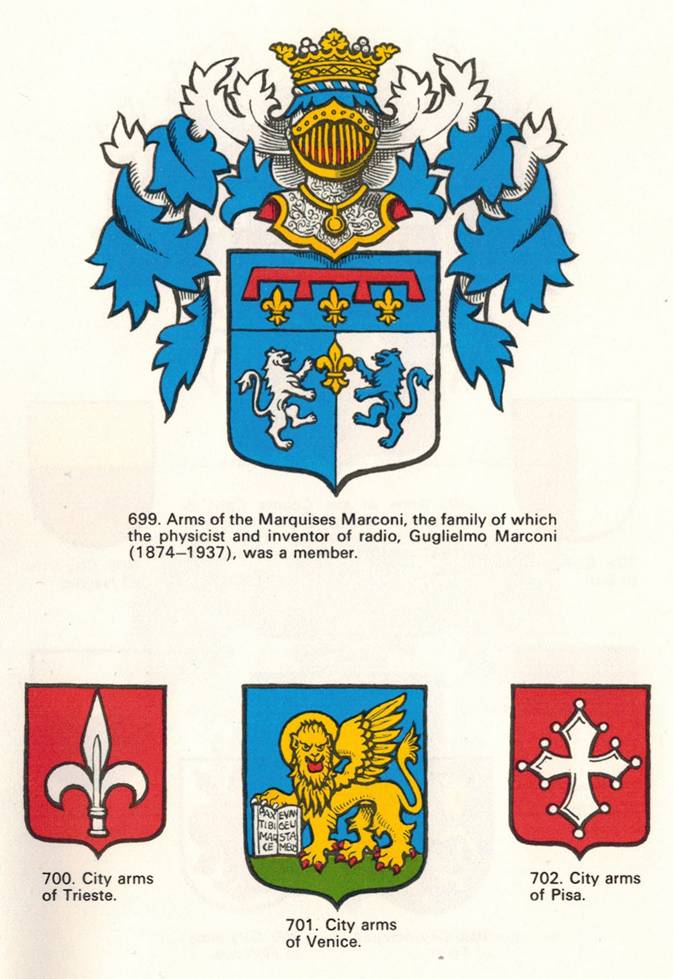

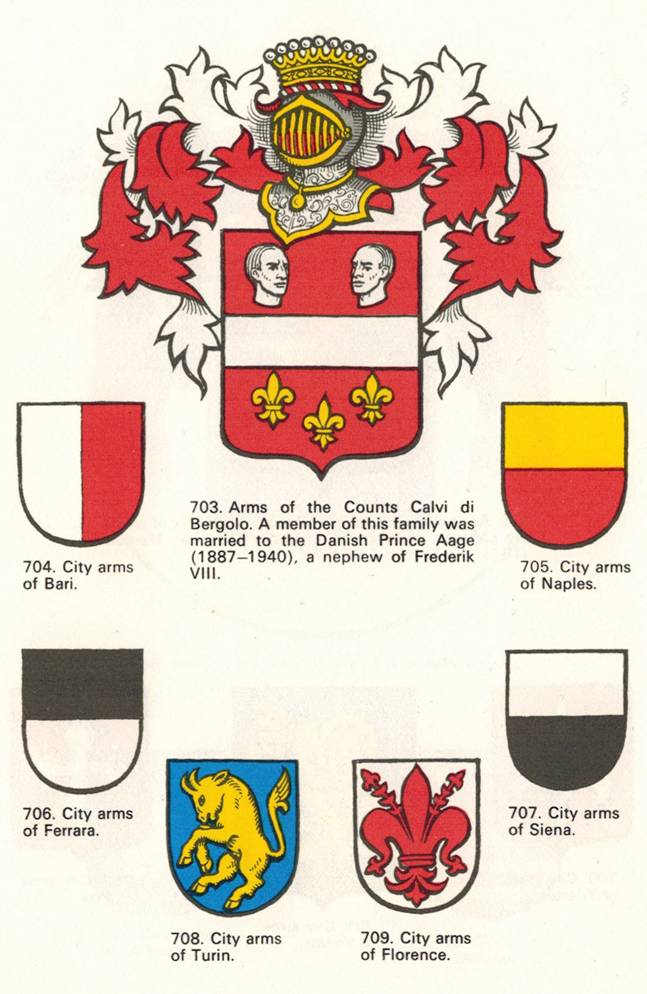

mantle (Figs 696 and 886), and this is not done in any other country. Civic heraldry is remarkable in its

simplicity (see p. 130). The cross is very common (p. 133), so common in fact

that two different towns sometimes have the same coat of arms. Initials are

also used quite often in civic coats, one example being Rome's (Fig. 674),

where the letters SPQR stand for Senatus Populusque Romanus, 'the

Senate and People of Rome'. Civic bearings are often ensigned by mural crowns (Figs 688 and 689) or by noble

coronets in memory of ancient privileges. Messina and Otranto even have a

royal crown. Supporters are rarer, but sometimes the shield is encircled by

branches of olive or oak. As well as the Collegio Araldico, 16 Via Santa Maria dell'Anima, Rome, those interested in heraldry can

communicate with the Istituto Italiano di Genealogia e Araldica, Palazzo della Scimmia, 18 Via dei Portoghesi, Rome. |

|

|