|

|

†††††† ††††† ††††† †††††† Excerpt from the book †† HERALDRY OF THE WORLD †††††† Written and illustrated by ††††††††† Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. ††††††††††††††††††† Copenhagen 1973 †††††† Internet version edited by† †Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Spain (pp.

120-123 and 211-213) Spanish heraldry contains various special

features which often facilitate the distinguishing of Spanish arms from those

of other countries. One of the most striking characteristics is the bordure,

which is very common, containing at various times castles, St Andrew's

crosses, lilies or a chain (see Figs 643, 659, 660 and 661). Some of these

bordered coats of arms originate from the time when the arms of a married

couple were combined by placing the husband's escutcheon in the centre of the

shield, with a miniature edition of his wife's ancestral arms, or a charge

from these, being arranged six or more times in a bordure around it. An

example of this can be seen in the royal arms of Portugal (Fig. 626); the

white shield in the centre is the original Portuguese coat of arms; the red

bordure with the castles comes from a marriage with a Castilian princess and

is derived from her paternal ancestral arms (see Fig. 639). Sometimes a motto

is included in the bordure and thus in fact on the shield itself (Fig. 655),

a thing that in other countries would be regarded as poor heraldic practice.

Another characteristic and very common

charge is a bend held in the mouths of two dragons or lions, as found in

General Franco's armorial bearings (Fig. 641).

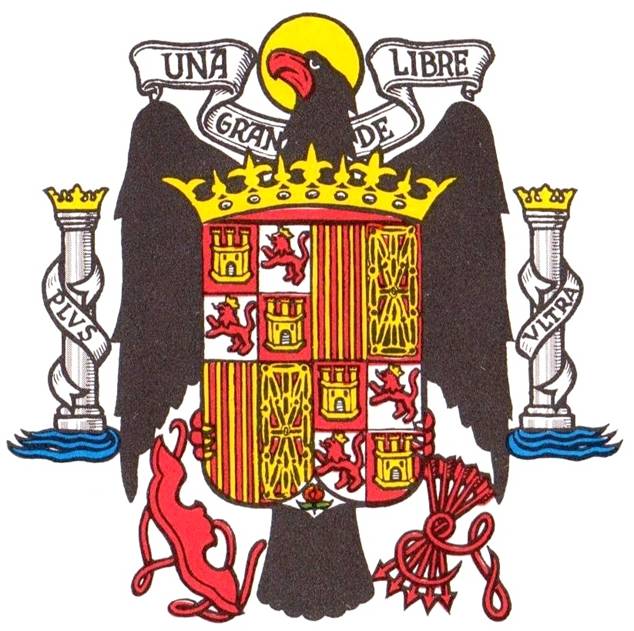

641. Arms of the

Spanish head of state, Francisco Franco. In heraldic art, as mentioned previously,

the 'metals' - silver and gold - can when necessary be replaced by white or

yellow. But the rule is that in the blazonry of a coat of arms either white and yellow or silver and gold are used and

not, for example, white and gold, or silver and yellow, or yellow and gold,

in the same arms. It is one of Spanish heraldry's specific features that this

rule is not necessarily followed, for not only may white and silver be used

in the same coat of arms, but they may be found one on top of the other. Thus

in Fig. 655 the bordure is silver while the motto it contains is white. The helmets of the royal family are gold visored helmets set affronty

with the visor raised (Fig. 647). Dukes and marquises have silver barred helmets

with the bars etc. in gold set affronty: A duke has

nine bars, a marquis seven (Figs 648 and 649).

Counts, viscounts and barons have the same

type of helmet but set in profile, the first two categories with seven

visible bars ó the difference in rank is shown by the coronet - the baron

with five (Figs 650, 651 and 652). A hidalgo, that is a gentleman of old

lineage without a title, may use the same type of helmet as a baron though

entirely in silver (Fig. 653) or, and this is probably more common, a mixture

of visored and barred helmet in profile with raised

visor and three visible gold bars (Figs 660 and 661). At times the mantling

is made to appear as if it were fixed to the interior of the helmet instead

of issuing from the top of it (see Fig. 49).

Titled aristocrats place their coronet on

the top of the helmet when one is used. Crests are rare and therefore the

helmet is often omitted. In that case a coronet may rest directly on the

shield. Untitled members of the nobility who do not have a coronet usually

retain the helmet and then use a few ostrich feathers as a crest, as a rule

in the same colour as the mantling (Figs 660 and 661). The arms of a grandee

(see p. 123) are mostly set within a red robe of estate lined with ermine

(Fig. 280). Since the eighteenth century it has been the custom for grandees

to place a red cap inside their coronets (Fig. 663).

Anybody may use supporters. They were

common in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but seem on the whole to

have been dispensed with nowadays. It is the custom in Spain to use the

surnames of both the father and mother, sometimes even those of the grandparents,

according to certain defined rules, and the same applies with coats of arms.

The coats one chooses to bear and the manner in which they are marshalled on

the shield have to be approved and registered with the heraldic registrar,

the Cronista de Armas

(see below). It is usual to include the arms of paternal

grandfather and maternal grandfather in the first and second fields of a

quartered coat of arms, and those of paternal grandmother and maternal

grandmother in the third and fourth. In the Middle Ages descent from four armigerous grandparents was the proof required for

recognition of a hidalgo's nobility. If one of the grandparents has no coat

of arms, one of the others can be repeated, or the shield can be divided into

three: once vertically and once horizontally. If there are more than four

coats, the shield can be divided up into a corresponding number of quarterings, or one or more coats can be included in an inescutcheon. In 1931, when King Alphonso

XIII went into exile, Spain became a republic for the second time (the first

was 1873-74), and titles of nobility and armorial bearings were abolished at

the same time. In 1939 the Spanish Civil War ended in victory for General

Franco, and in 1947 he declared that Spain was again a kingdom (although

without a king for the time being). In 1951 an office was established under

the Ministry of Justice which was to register and supervise the heraldry of

the country. The officials in control of this work are

no longer called Kings of Arms and heralds, as they were formerly, but

'heraldic registrars' - Cronistas de Armas. There are five of them, probably one for each of

the five historical kingdoms which make up Spain: Castile, Leon, Aragon,

Navarre and Granada (see Fig. 639). The registrars hold office for life and

deal not only with the country's heraldry but also with questions regarding

titles of nobility and so on. A coat of arms is in Spain protected by

law, and misuse is punishable. Only arms registered with a Cronista de Armas

can be publicly displayed, but anybody, including a commoner, can register

his arms or request the authorisation of a newly composed coat of arms.

Whether earlier heralds' patents of arms also conferred nobility has been the

subject of much discussion, but a 'certificate or arms' from a Cronista de Armas certainly

does not do so. People in former Spanish colonies, e.g. the

Americas and the Philippines, who are not necessarily of Spanish descent, can

also register an existing coat of arms or obtain a certificate for a new one

from the registrars in Spain. The civic arms of Valencia and Barcelona

are set on a lozenge-shaped shield following an old tradition (Figs 644 and

646) that probably has no parallel elsewhere. Instead of the coronet of a

marquis on Valencia's shield a royal crown is sometimes used. The mural crown

(Fig. 642) was used especially during the time of the two republics (1873-74

and 1931-39), but since then has been replaced almost everywhere by other

types of crown.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||