|

|

Excerpt from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||

|

|

England (pp.

60-68 and 191-192) Great Britain differs from other countries

in that there are heraldic officers who still perform their function, and

heraldic regulations which still pertain. This latter is particularly true of

Scotland. The heraldic authorities hold the view that no coat of arms can be

assumed as a matter of course; it must be assigned or be confirmed by them.

Some heraldists insist that a legally granted coat

of arms endows the bearer with a form of nobility, but this is not generally

accepted (see p. 181). The College of Arms controls England's heraldic

administration. At its head is the Earl Marshal, an office which is

hereditary in the family of the Dukes of Norfolk (Fig. 291). The most

important of the heraldic officials proper is Garter King of Arms (see p.

180). In Scotland Lord Lyon King of Arms (his name is taken from the royal

arms of Scotland) is the highest heraldic authority. His is a royal

appointment and he himself appoints the other Scottish heralds and pursuivants (see p. 180). In England all kings of arms, heralds and pursuivants

are appointed by the reigning sovereign. Ulster King of Arms formerly had

authority over the whole of Ireland. Now his jurisdiction is limited to

Northern Ireland (the office being combined with that of Norroy

King of Arms), while the Republic of Ireland (Eire) has its own Chief Herald

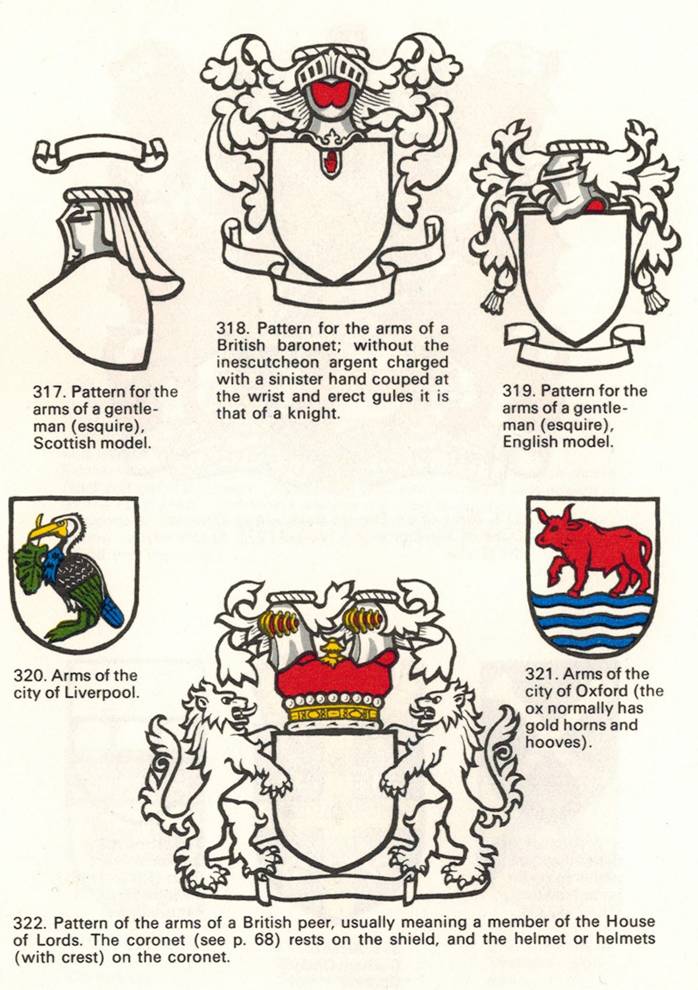

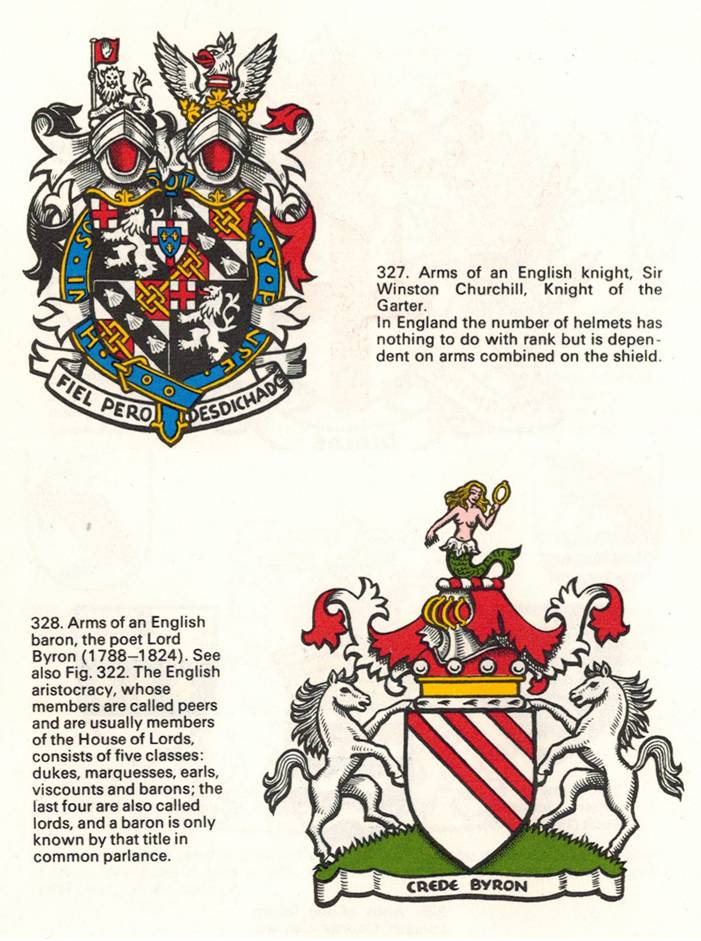

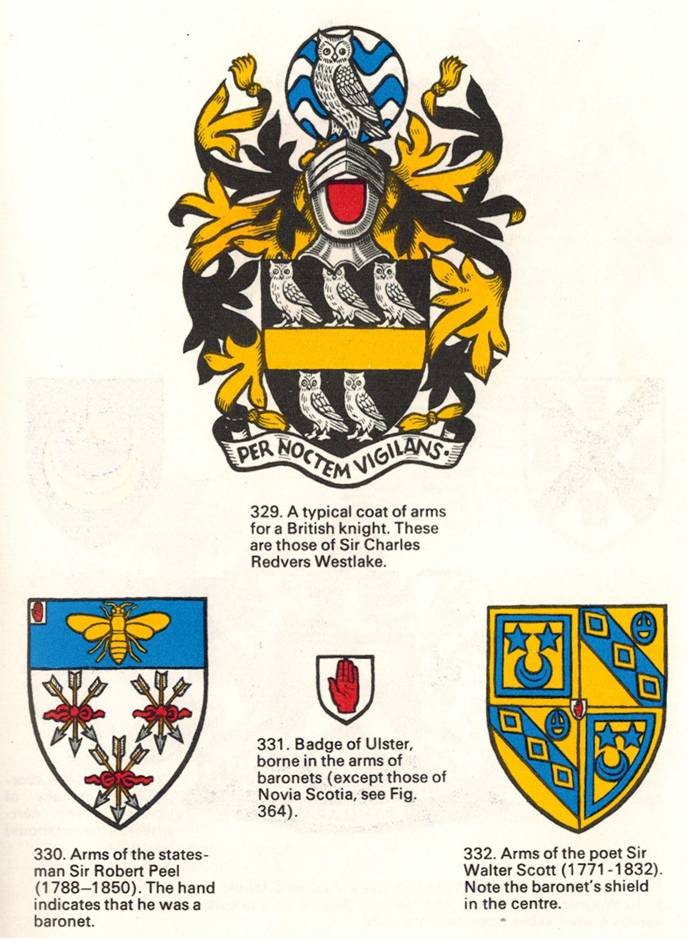

of Ireland. Another thing particular to Britain is the

title of baronet which ranks below the peerage. A baronet inherits the title

of Sir, in contrast to a knight, who only holds this title during his own

lifetime. Baronets and knights bear the same characteristic helmet in their

arms: set affronty with raised visor (see Figs 48,

318, 327 and 329). The rank of baronet was introduced in 1611 by King James I

in connection with the conquest and colonisation of Ulster, and this is why

the arms of baronets (other than those of Nova Scotia) include a small shield

with a red hand on a white field (Figs 330, 331 and 332), derived from the

coat of arms of Ulster (see Fig. 375). From 1625 certain Scottish baronets

were given the attribute ‘of Novia Scotia’ in

connection with the colonisation of this region on Canada’s Atlantic coast (see

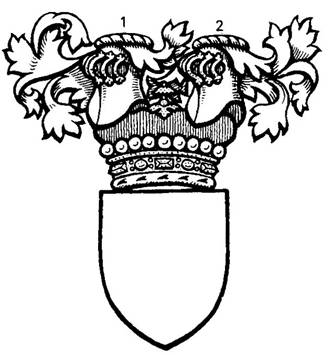

Fig. 364). Helmets are used according to strict rules.

The royal helmet, borne by Queen Elizabeth and the royal princes, is a barred

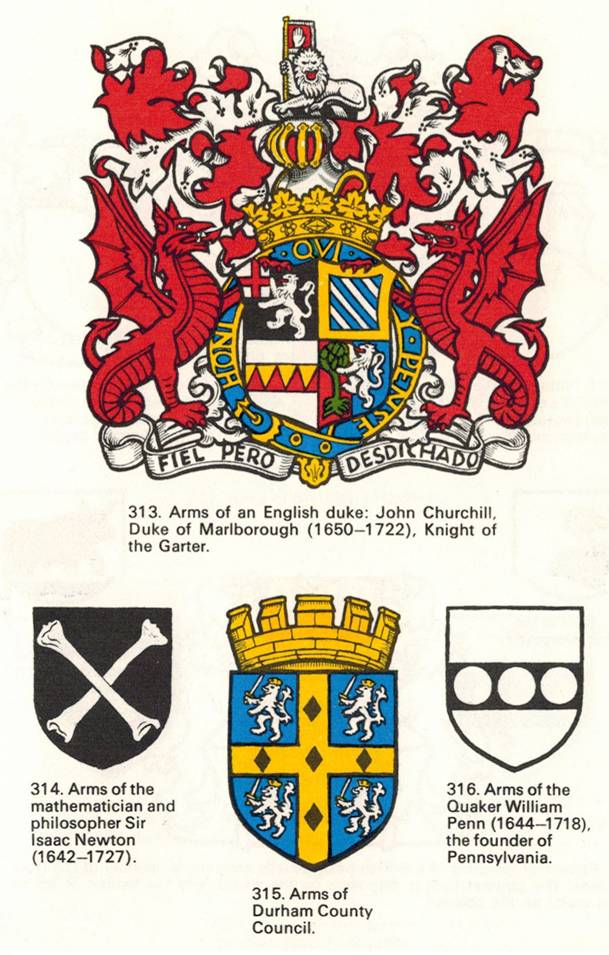

helmet in gold, set affronty (Fig. 225). Peers bear

silver or steel-coloured barred helmets with gold ornamentation, in profile,

so that five bars can be seen (Figs 57, 272, 313, 322 and 328). The helmets

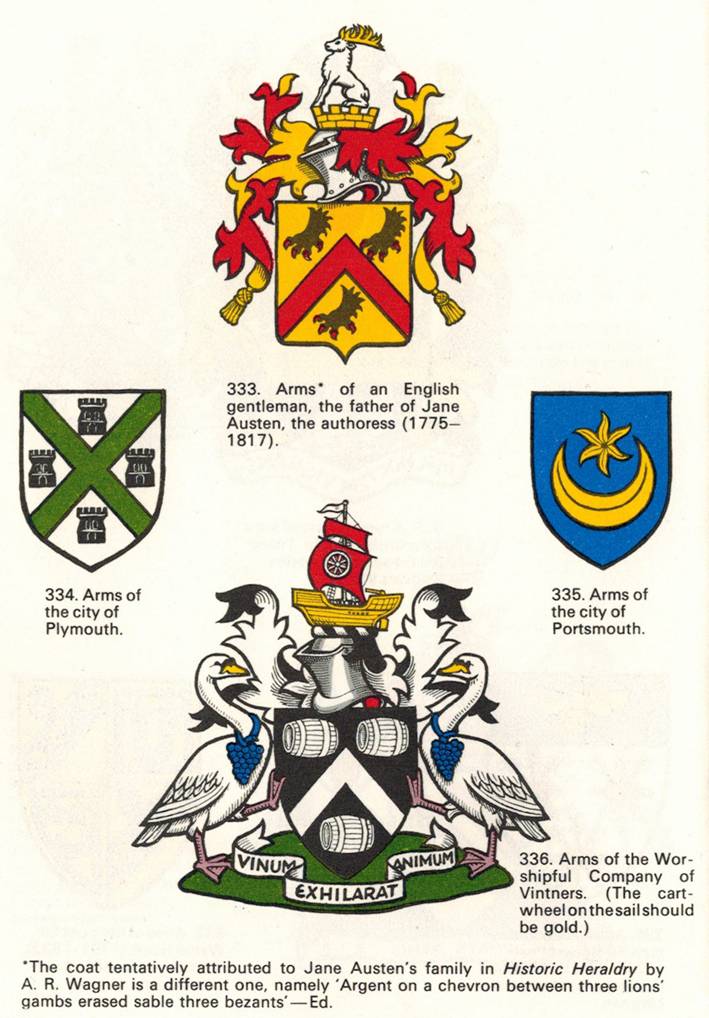

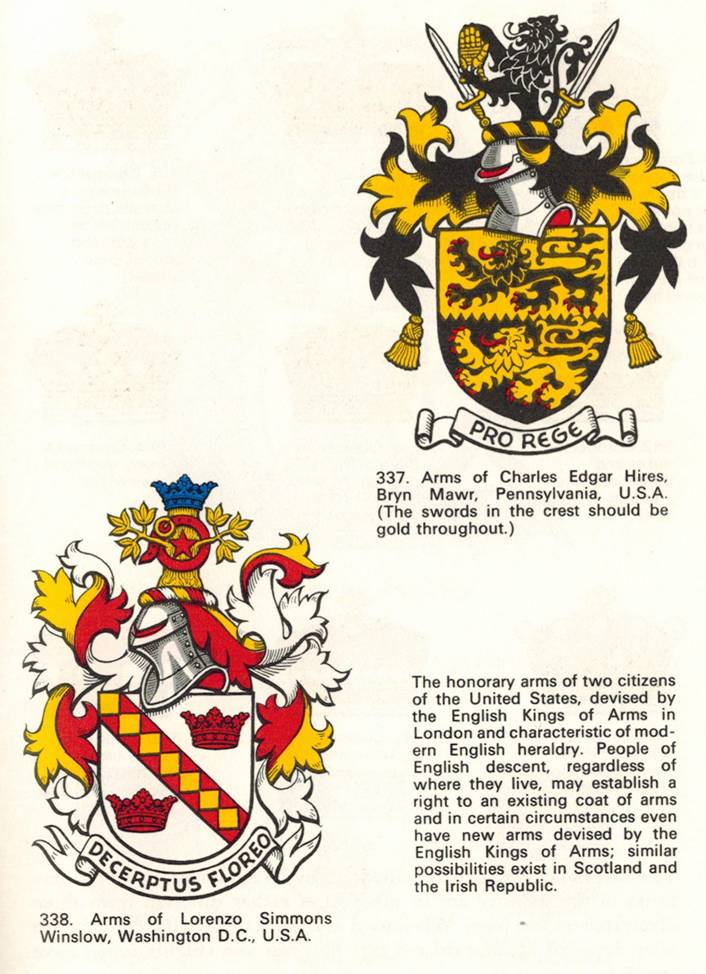

of baronets and knights have already been mentioned. On the first rung of the

ladder of rank is the gentleman or esquire (the two ranks were previously

distinct and to some extent still are), who bears a steel-coloured tournament

helm, set in profile (see Figs 333, 337, 338, 376, 385 and 386). Formerly a visored helmet was often used as shown on p. 19, but nowadays

the jousting helm without visor is generally preferred.

The inside of a helmet is usually red but

may be of other colours. If there are two or more helmets they generally face

the same way, i.e. to the dexter (see Fig. 57), not

towards one another as is the style on the Continent. The rule about the

position of the helmet - in profile or en face - depends on the owner’s rank

and often makes it difficult for the heraldic artist to make sense of a coat

of arms: a baronet’s helmet should be depicted en face, even though the

corresponding crest should really be shown from the side; a peer’s as well as

a gentleman’s helmet is usually shown in profile, regardless of whether the

corresponding crest might best be shown en face. The mantling in the arms of Queen Elizabeth

and the Prince of Wales is gold on the outside, ermine on the inside (Fig.

225). The other members of the royal family wear gold lined with silver. In

Scotland peers and certain high officials have red mantling lined with ermine

(Fig. 366), while the wreath is of the livery colours, i.e. the shield’s

principal metal and colour. Otherwise the mantling is usually of the livery

colours. In Ireland the mantling is often red with white lining (see Figs

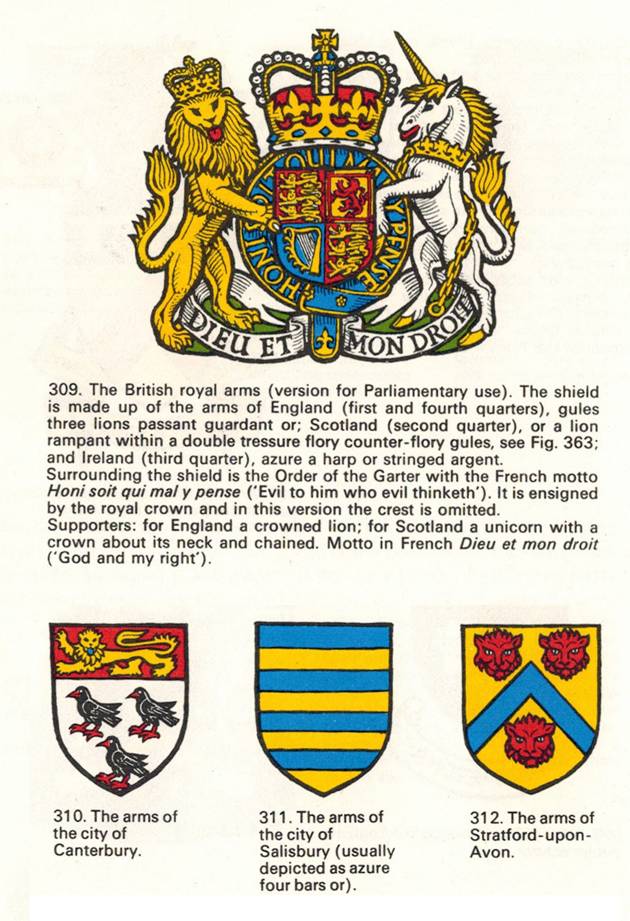

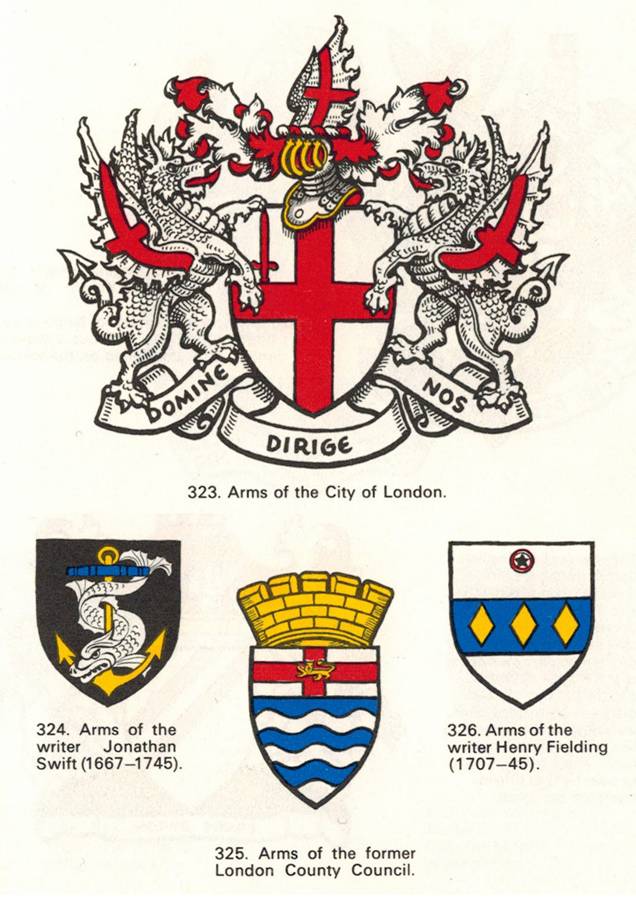

376, 385 and 386). In England supporters are used as a special

mark of distinction only accorded to specific categories of persons or

institutions. In England they are reserved for the royal family, secular

peers (bishops and archbishops do not have supporters), Knights of the

Garter, and Knights Grand Cross of other orders, and also for boroughs,

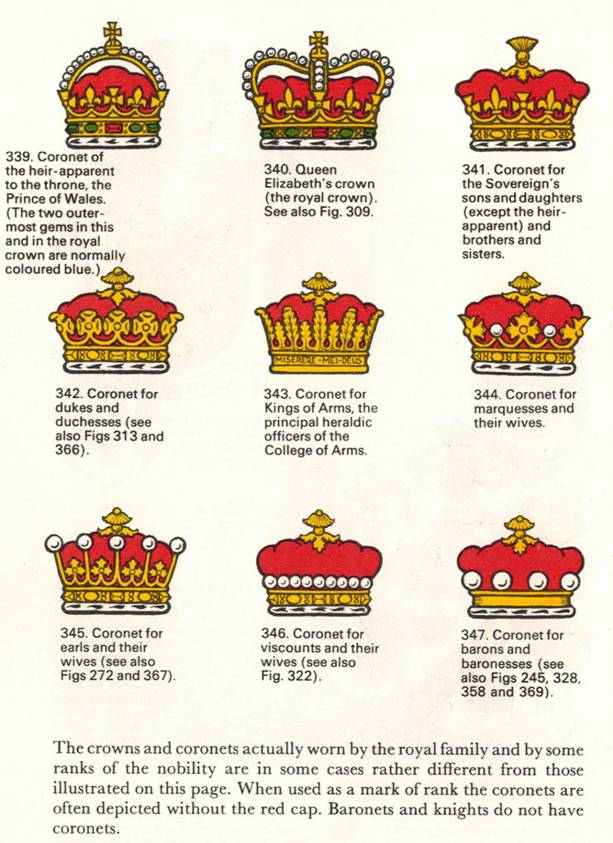

counties and certain institutions (Figs 272, 313, 323, 328 and 336). Crowns and coronets are in Great Britain

generally used only by the royal family and the peerage. They are placed

above the shield (see Figs 57, 313, 322, 328 and 366). The coronet usually

encloses a crimson cap topped by a gold tassel and edged at the base with

ermine which is visible below the coronet (p. 68). The helmet and the crest

are placed above the coronet (Figs 57 and 313). In Belgium the coronet is

borne in a similar way (Figs 422 and 423), but most other countries either do

not use coronets together with helmet and crest or else set the coronet on

the helmet (Sweden, Poland, Italy, Spain, France). In Central Europe both titled and untitled

nobility and sometimes commoners too use a coronet on the helmet which is not

a sign of rank (see pp. 18 and 40), but in Great Britain this is rare. In

Scotland a crowned helmet can be granted to the heads of certain families.

Feudal barons can bear a chapeau or ‘cap of maintenance’ (see Fig. 217).

Another special feature of British heraldry

is the system of distinguishing various members of the same family with the

aid of individual marks of difference introduced into the basic coat (p. 72).

The idea behind it is that a coat of arms should identify its bearer, so that

a father and son, or two brothers, do not have exactly the same arms. Similar

‘cadency marks’ have been used on the Continent

usually, but not always, among princes and the high aristocracy, but they

have never been popular and in most countries went out of use long ago. This is to some extent the case in England

too (apart from the royal family), although the practice has been more

prevalent and has remained in use longer than in the rest of Europe. The

principle is (or was) that only the head of the family bore the arms without

a difference. When the father died, the eldest son took over these original

arms by removing the symbol for an eldest son, as a rule the label (Fig.

370). Younger sons on the other hand retained their cadency

marks and sometimes these were passed on, with or without further

differences, to their descendants. In the course of two or three generations

however the system soon becomes so involved and overloaded that it becomes

unworkable. Cadency marks can be

depicted in any tincture though the ‘colour rules’ (p. 23) should be adhered

to. Silver (argent) labels are now generally considered to be the privilege

of the royal family; the Prince of Wales has his undecorated, while other

members of the royal house vary theirs with roses, crosses, anchors etc. In addition to the official bodies Great

Britain has a large and active heraldic association - The Heraldry Society,

28 Museum Street, London W.C.l.

|

|

|