|

|

Excerpts from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written

and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth ,

K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited

by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

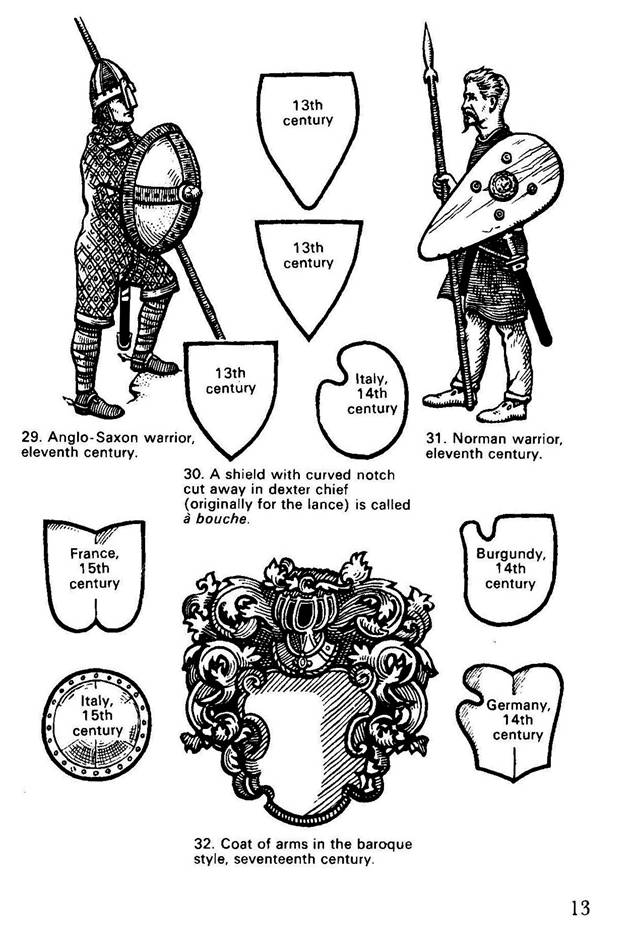

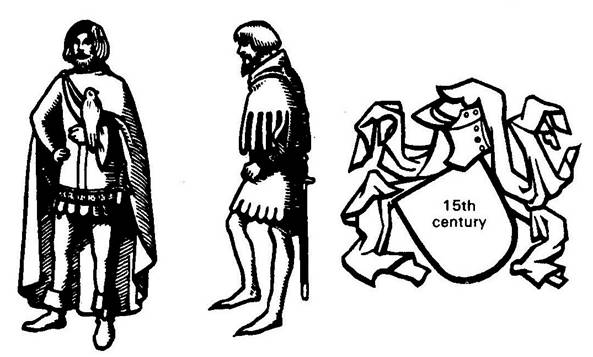

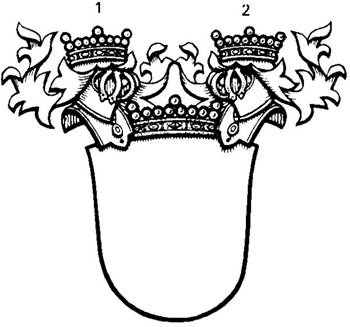

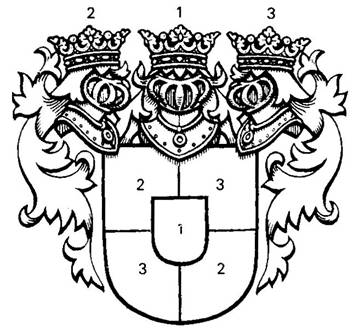

Shields and Helmets (pp.

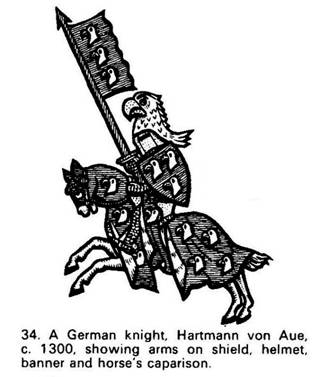

182-182 and 11 - 22) A warrior could put his emblem on all parts

of his equipment (see Fig. 34), but the shield with its large solid surface was

the best suited. It was usually made of wood covered with leather or

parchment (sometimes covered in canvas above this) on which the device was

painted. The emblem could also be embossed in low relief in the leather

itself or picked out in metal studs. When in use as defence, the shield was

carried on the left arm, supported by straps at the back of the shield. When

not in use it hung at the left side by a strap over the right shoulder.

Throughout the whole of the Middle Ages it was common to show a coat of arms

in a slanting position, just as it must have looked hanging at the warrior's

left side (see, e.g., Fig. 22 and p. 17). Occasionally it was depicted

suspended by its strap and hanging from a tree.

The earliest form of shield in heraldry was

the elongated, kite-shaped Norman shield (see Figs 31 and 33). Examples have

been found on seals from the twelfth century and from an enamelled and

engraved tomb plate which shows Geoffrey Plantagenet (of Anjou) with gold

lions on a blue shield. According to a contemporary chronicle he was granted

this coat of arms by Henry I of England when he was knighted in 1127.

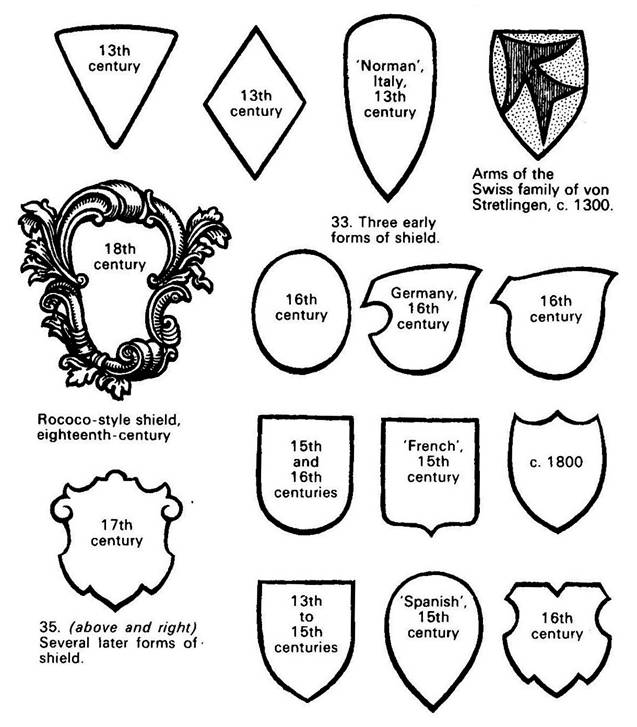

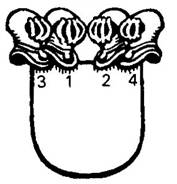

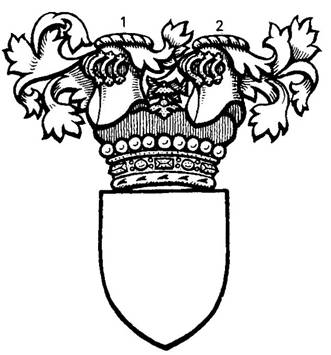

The

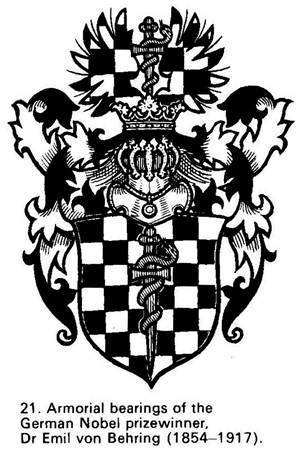

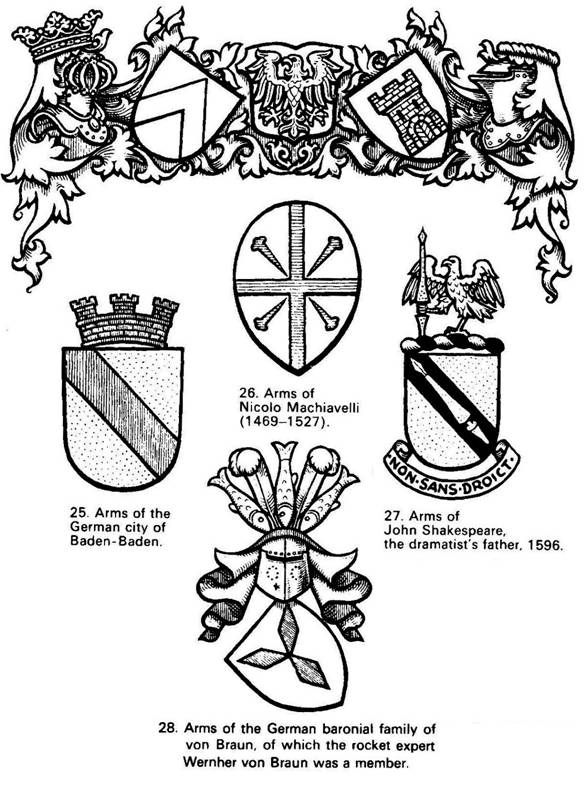

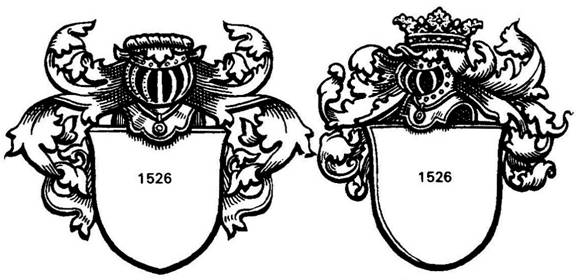

shield is the most important part of a coat of arms. It can take practically

any form, depending on period, place, function, situation or the whim of the

heraldic artist. Examples are shown on the following pages. A shield can be

used on its own (Fig. 26), with a crown above (Fig. 25), with helmet and

crest (Fig. 28), or with crest alone, without helmet (Fig. 27). Heraldry however followed the changes in

style and fashion, and this is reflected in the varying forms of shield (see

pp. 13 and 14). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries particularly,

during the periods of the Baroque and the Rococo, when the shield was no

longer used for practical purposes but was merely continued in graphic form,

decorative and distorted shapes far removed from a shield's original function

were invented. The heraldic artist of our time must for each occasion consider

seriously which form of shield he intends to use and should make it a rule

from the aesthetic point of view especially to base his work on the early

forms of heraldry in preference to the second-hand heraldry of later times.

The same is of course true for the helmet and other heraldic appurtenances.

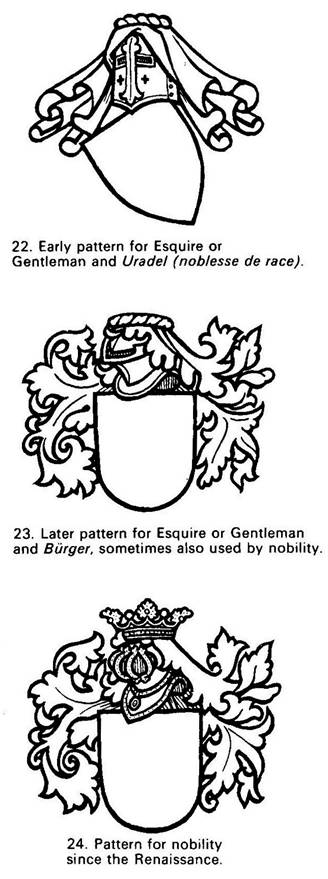

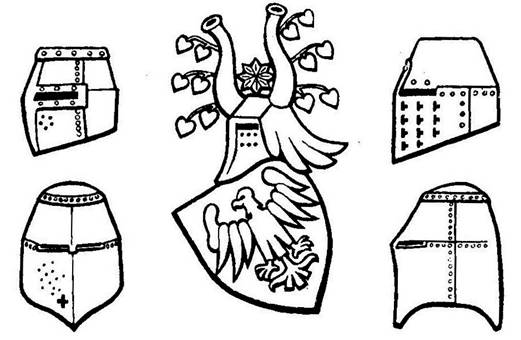

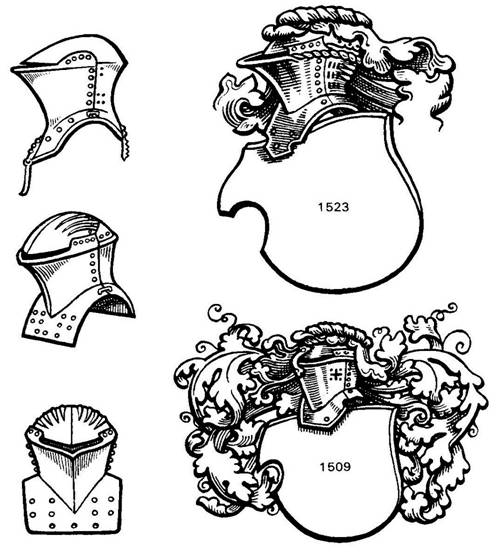

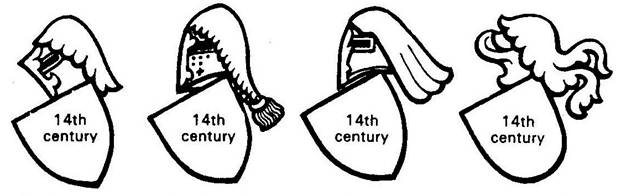

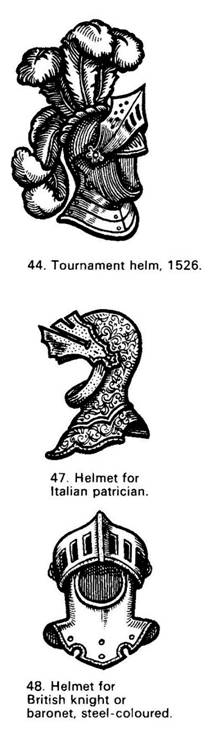

The helmet too has taken on different forms

in different periods. The oldest type in heraldry is the barrel helm, also

called the great helm (see p. 15). It was worn with a hauberk which also

covered the neck and head of the warrior, and it was by degrees furnished

with horns and other embellishments (see Fig. 36). When the warrior was not

fighting, the helmet usually hung at his saddle.

36. The earliest form of helmet used in heraldry,

going back to the thirteenth century, was the pot helm which usually had a

flat top. Around 1300 it was gradually replaced by the great helm which had a

conical top and rested on the warrior's shoulders. With this helmet the crest

came into general use. From the end of the fourteenth century it began to be

replaced by the tilting helm (see next page). In Scotland the great helm is

used by gentlemen and esquires regardless of the antiquity of the arms, but

in most other countries it is generally used only with arms which can be

traced back to the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries.

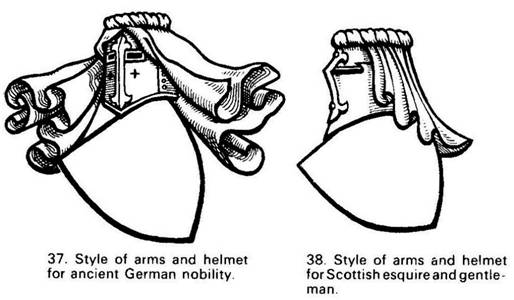

The good heraldic artist does not mix

elements of different styles, and a barrel helm should therefore be used only

with the forms of shield and mantling which belong to the same period, i.e.

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. For the same reason the coronet

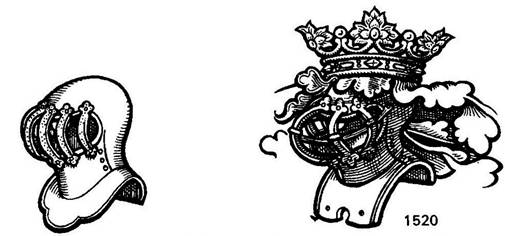

should not be used together with the barrel helm. Around 1400 the barrel helm was replaced by

the tournament helmet (see p. 16) and in the course of the century this again

by the barred helmet (see p. 18). In Spain, Italy and France the number of

bars indicated the bearer's rank. Around the neck-piece of the barred helmet

there often hangs a chain or a ribbon with a medallion. A variation of this

type of helmet has the bars replaced with a grating or lattice-work of metal

wire. TOURNAMENT HELMET (OR JOUSTING HELMET)

39. The tournament helmet derives its name

from the tourney or tournament, i.e. fighting with lances as a form of sport.

It came into use about the beginning of the fifteenth century and it was used

in heraldry for several centuries, in non-aristocratic arms especially. HELMET AND MANTLING

40. Mantling was originally a piece of

material fastened to the top of the helmet and hanging down over the warrior's

neck and shoulders, possibly to protect him from the heat of the sun.

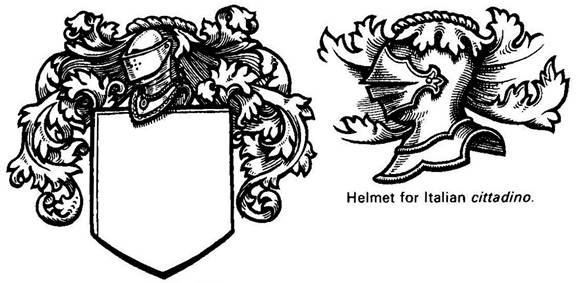

The visored

helmet became popular in the sixteenth century and is still used in certain

countries with the visor either open or closed (pp. 19 and 20). In Central

Europe, Germany and Scandinavia, however, it seems to have fallen out of use

completely. In some countries the position of the

helmet indicates the rank of the bearer. In England the golden helmet of the

royal arms and the helmet in the arms of a baronet or knight must be shown en

face (see Figs 48 and 225), while all other ranks show the helmet in profile

(facing dexter). In France, Spain and Italy a

helmet shown en face indicates the highest ranks, from marquis upwards. Most

other countries attach no importance to the position of the helmet, the crest

being the determining factor. The inside of the helmet is usually red, but

may also be of another colour, when for example it corresponds with the field

of the shield.

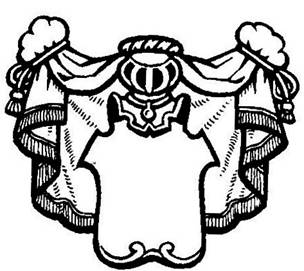

During the centuries the mantling of the

helmet has become one of heraldry's most decorative effects (see pp. 11-22)

and to exclude it when a coat of arms includes a helmet is considered

incorrect heraldry. The details of the mantling's

shape depend on the position and proportions of the coat of arms and on the

desire of the artist, but in every instance some part of both sides of the

mantling must be shown. Its tinctures are as a rule the same as the shield's, the most important 'colour' being on the outside

and the most important 'metal' on the inside - though there are many

exceptions. HELMET AND ROBE OF ESTATE

.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||