|

A

|

Excerpts from the book HERALDRY OF THE WORLD Written

and illustrated by Carl Alexander von Volborth , K.St.J., A.I.H. Copenhagen 1973 Internet version edited

by Andrew Andersen, Ph.D. |

|||||

|

|

The Aims and Contents of the Book (pp. 177 - 179) Heraldry

of the World

is not a reference book on all coats of arms in existence. It contains less

than a ten-thousandth, perhaps even less than a hundred-thousandth, of the

arms to be found in the world. It might be better to call it a condensed

heraldic dictionary containing characteristic examples of all important

heraldic phenomena characteristic, that is, both of the system itself (shield

and helmet, charges, supporters etc.) and of each country's interpretation of

it. This latter is the important point. There

are plenty of books on heraldry, in the principal languages especially, but

most of them are written from a narrow, nationalist point of view dealing

with the heraldry of only one country. What has been lacking is an

international guide to heraldry, with a survey of the subject in all

countries. Since no such book has appeared in recent years, the author

decided to write and illustrate one himself. The result is the book you have

in your hands. One of the things that surprised the author

when he came to grips with his undertaking was how great in fact the

differences are in the heraldry of the various countries with regard to

custom and usage, rules, style and taste, but this of course was only a

further incentive to continue the work. Furthermore, heraldic art and style

are in a constant process of development. The heraldic taste in Scandinavia nowadays

has a clear leaning towards the abstract, while in Spain and Italy heraldry

moves increasingly towards a naturalistic style. In Germany and France on the

other hand traditional heraldry continues even now with its stylisation

according to late Gothic and early Renaissance models. In heraldic art it often happens that a few

professional and popular heraldic artists influence, by their particular

style, their own age, and posterity, to such an extent that the elements of

it become characteristic of the nation to which they belong. In Germany this

is particularly true of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528),

Hans Burgkmair (1474-1531) and Jost

Amman (1539-91), the work of all of whom has been a great inspiration to the

author of this book. But since the aim is not to show the best artistic

examples of coats of arms but rather those most typical of a nation or an

epoch, the author has deliberately not followed his own personal taste but

has tried to copy characteristic models as closely as possible. A nation's heraldry reflects its historical

and cultural development. Throughout the history of Europe, from the

beginnings of heraldry up to our own times, national frontiers have shifted

time and again, often as the result of war, but also for example through

marriage or inheritance. And when a country increased its territory or its

influence in some other way, its heraldry as a rule followed suit. This is

the reason for indications of German, French and Spanish heraldry found in

Italy side by side with the various forms of its native heraldry. This again

is of course the basis for colonial heraldry and its special differences. One

exception is the complicated heraldic system thought up by Napoleon which did

not survive him. Families and towns with a Napoleonic coat of arms have as a

rule adapted this later to be more in keeping with their homeland's

time-honoured heraldry. The French Revolution from 1789 onwards

abolished not only the lilies of the royal house but also all other French

coats of arms, only to introduce its own system of emblems and symbols. In

presentation these differed considerably from the traditional and were really

just a new form of heraldry. Something similar occurred in North America

after the War of Independence, 1776-83, and in South America after the

break-away from Spain at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Although

some leaders of the North American revolution possessed coats of arms and

used them, as in the case of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, it was

gradually considered undemocratic and snobbish to bear arms in the United

States. The bearings which were devised for constituent states or cities

rarely had any similarity to traditional arms and are called 'seals'. Latin America's heraldry also diverged from

the well-established European standard, but this was not only for political

reasons. Most national emblems in South and Central America were created at a

time when heraldry as an art form was not of consequence anywhere in the

world. Some of them can hardly be called coats of arms at all. Canada is an exception. Its long

association with Great Britain, first as a colony and later as a member of

the British Commonwealth, resulted in British customs and usages with regard

to heraldry being followed. In Communist countries from East Germany to

China, following the revolution in Russia in 1917 and even more so after the

Second World War, a completely new and rather uniform series of state emblems

has developed which in their presentation differ completely from the earlier

arms of these states. Yet on the other hand traditional heraldry flourishes

in many new and to some extent revolutionary states, as for example in

Africa. Thus heraldry is in fact an international

phenomenon, but it has very characteristic national and political

differences. And that is what this book sets out to

demonstrate. Some readers may think it strange to find

so many symbols of nobility, such as coronets and the like, in a modern book

on heraldry. But we must not forget that heraldry in its origins is an

aristocratic phenomenon and that such symbols are a part of its history.

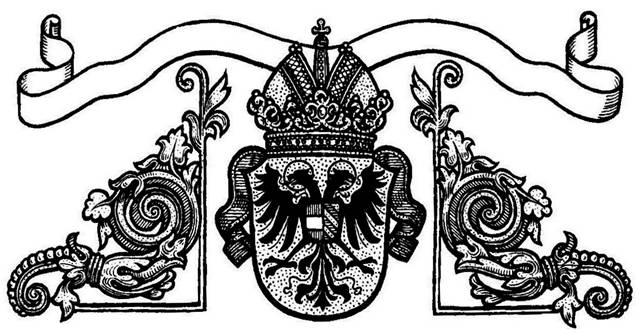

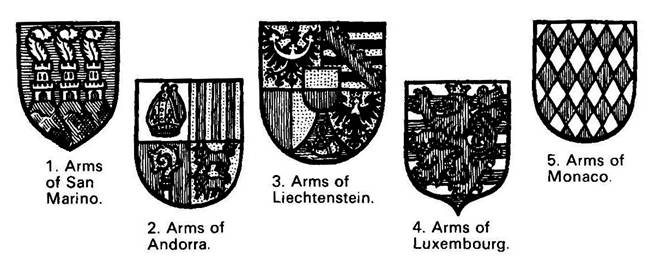

The Origins of Heraldry (pp. 7-9 and 179) The

coat of arms above belonged to Archduke Maximilian of Austria who became King

of the Romans in 1486 and, as Maximilian I, Emperor 1493-1519. The two halves

of the inescutcheon stand for Austria and Burgundy. The origin of heraldry among warriors as a

form of decoration for their equipment is reflected in the two meanings of

the word 'arm'. To differentiate between these two expressions the plural

form 'arms' is used in heraldry. The arm of the warrior is his sword or

lance, his arms are his emblems. There is a similar connection in other

languages too. The German Waffen refers to a weapon for offence or defence, Wappen refers

to his coat of arms. The expression 'coat of arms' actually originated in the

surcoat bearing an emblem which the warrior wore

over his hauberk (see Fig. 34).

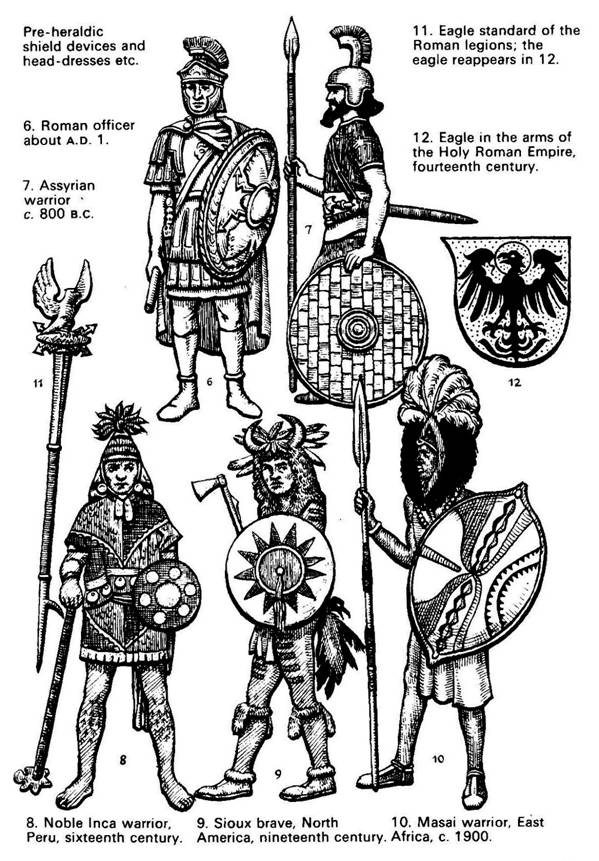

It was during the early decades of the

twelfth century, between the First and Second Crusades,

that nobles, knights and princes began to identify themselves and

their equipment, their shields in particular, by the use of simple figures in

clear, contrasting colours, and this must be considered the origin of what is

now called heraldry. For warriors to decorate themselves and their shields

was certainly nothing new; it had been a feature of almost all ages and

cultures (see p. 9), in Europe as well as elsewhere, since long before the twelfth

century. The particular characteristic of these new shield devices was the

fact that they remained more or less the same for each individual and then

gradually became hereditary; that their use was extended to practically all

classes and institutions in the community; and that this developed into a

detailed and permanent system for the elaboration and application of the

insignia within a short time.

The earliest arms were adopted at will by

the individual, but from about 1400 onwards sovereigns began to grant

insignia by means of letters patent, often, but by no means always, as the

prerogative of the nobility. Families whose nobility originates in such

letters patent or in similar elevations or creations are said to hold patents

of nobility; the older aristocracy, whose origins are lost in the darkness of

the Middle Ages, is known as the (old nobility'. But concurrently with the

granting of insignia by letters patent, people continued to assume insignia

for themselves and, provided that devices were used that were not already the

prerogative of others nor resembled another bearing too closely, this was

tolerated, at least in the Middle Ages in most European countries. From the warrior class the practice spread

to the Church, to burghers and farmers, and to municipal governments, craft

guilds and other institutions. Almost from the beginning of heraldry women

too had the right to bear arms. (See also pp. 42-4.)

The Origins of Heraldry; Heraldic Charges (pp. 7-8) What were the origins of these new devices? For the warrior class there were three main

sources of inspiration: the banners and standards that already existed in the

pre-heraldic period, the purely functional plating or reinforcement given to

the shield - nails, ridges, strips, crosses, etc. - and finally what might be

called totemic signs: figures, often of animals or fabulous beasts,

expressing chivalrous ideals, such as warlike lions, eagles, falcons,

unicorns, and so on. For princes and the Church many devices

were probably derived from seals, the use of which antedates heraldry proper,

or from religious symbols. It was also natural for people of various stations

to choose devices relevant to their profession or way of life. The bishop

included a crosier in his escutcheon, the priest a chalice, the squire a

spur, the brewer a barrel, the smith a hammer, the fisherman a fish trap, and

so on. A large number of these were what are

called 'canting arms', i.e. they illustrate or refer to the bearer's name, for

example a falcon for the name Falconer, or hirondelles - swallows - for

Arundel. Further reference will be made to this on p. 34. It must also be mentioned that many arms

were adaptations or imitations of existing coats. Armorial bearings of cities mostly fall

into seven categories relating to their origins. Many city arms show the city

itself or a dominant part of it: the city wall, the gate, a castle, church,

bridge or tower. In another large group, the arms include a

figure representing the city's patron saint or the saint's attribute. Other

armorial bearings reflect the city's livelihood, its most important product

or export. Hence we find herrings, bales of wool, bunches of grapes etc. or,

more recently, two crossed pencils, the wheels of a locomotive, or the two

crossed shrimps of Christianshaab in Greenland, a

symbol of the city's canning industry. Related to the above are city coats of arms

which have developed from the seal or device of the city's most important

craft guild or from that of some other trade organisation. One example is the

coat of arms of Paris (Fig. 429). The captains of river craft played a

dominant role in the city in the Middle Ages, and the device in their guild's

seal and the emblem of the guild were gradually (in combination with the

royal lilies) accepted as the bearings of the city itself.

429. City arms of

Paris. Some city arms can be traced back to military

standards or banners used by the citizens in battle or in defence of their

city. This is true of a number of cities and cantons in Switzerland (see pp. 112 and 113). Some ancient towns, particularly in Germany

and England, have armorial bearings which are identical with, or a variation

of, those of the prince or nobleman on whose land they were built and whose

protection they enjoyed. A Danish example is Naestved,

built on land owned by the Catholic Church, which includes the papal emblem,

two crossed keys (see Fig. 879) in its coat of arms. Finally there is a large group of civic

arms which are allusive, i.e. containing a charge which makes a play on the

name of the town (see also page 34). The city of Lille has a lily, the city

of München (Munich), a monk (German: Moench), and so

on. When councillors or other burghers assumed

coats of arms, they were often inspired by the arms of their city which in

this way were continued in many variations as well as in their original form.

. |

|

||||